WATCH | Sam Hickey asks what do you get from a political settlements perspective?

Professor Samuel Hickey recently spoke at the University of Edinburgh Political Settlements Research Programme Summer School, on the comparative insights into the politics of development in Africa.

We’re looking for a lecturer in Information and Communication Technology for Development

The Global Development Institute is looking for a permanent lecturer in Information and Communication Technology for Development. We are looking to appoint an outstanding individual who willmake a central and strategic contribution to, and enhancement of, our research and teaching programmes in the information systems/ICTs and development domain. You will also have a definable area of research and teaching interests that will complement those already present within the Development Informatics Group and the wider context of GDI; and direct experience of digital systems in developing/emerging economies through development of or research into such systems is essential for this post.

The Global Development Institute is looking for a permanent lecturer in Information and Communication Technology for Development. We are looking to appoint an outstanding individual who willmake a central and strategic contribution to, and enhancement of, our research and teaching programmes in the information systems/ICTs and development domain. You will also have a definable area of research and teaching interests that will complement those already present within the Development Informatics Group and the wider context of GDI; and direct experience of digital systems in developing/emerging economies through development of or research into such systems is essential for this post.

Applications close 29th September 2016

The Africa Agenda 2063 and the SDGs: the African Union barks, but will it find its bite?

Fortunate Machingura, former PhD student at the Global Development Institute

This blog has been republished from the Overseas Development Institute and was written by Fortunate Machingura, a GDI alumna who completed her PhD in Development Policy and Management earlier this year. Fortunate is now a Research Fellow for the Development Progress project at ODI.

The African Union (AU) is often described as a ‘toothless bulldog’ withcredibility and legitimacy deficits. But its recent work may be indicative of a changing status. Through the Africa Agenda 2063(AA2063) – a framework reflecting African solutions to its problems – the AU appears to challenge western hegemony on global development and, in the process, has laid down two significant markers of change.

Firstly, at a joint conference with UNECA in Addis Ababa in April 2016, the AU embraced an integrated approach to the implementation and tracking of the AA2063 and the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Building on the common African position on the post-2015 development agenda , the conference agreed on a single periodic progress report on both agendas, and to step up efforts to combat corruption. Secondly, the AU is trying to tackle the fragmentation of its states through a continent-wide approach that centralises decision-making and speeds up development progress.

This new approach represents an emerging narrative of African solidarity and political tenacity, which has the potential to lead to greater freedom of movement, reduced trade barriers and coordinated efforts to tackle problems of social, economic and political capital. For example, coordination between oil-rich countries (e.g. Ghana and Nigeria) and the African ores (e.g. the Democratic Republic of Congo, Botswana, South Africa, Tanzania) could provide unprecedented economic opportunities due to the huge labour market coupled with a youthful population.

For these developments to be realised, however, it is imperative that there are mechanisms that recognise these new patterns of political connection and solidarity among African states and global partners. While the recent Côte d’Ivoire high-level political forum on SDGs and the April 2016 New York high-level forum on Africa are examples of recent efforts to strengthen solidarity with Africa and beyond, more is needed to translate these high-level political forums into real actions that help the most impoverished communities.

While these platforms were progressive, they must also be recognized as taking place during a political conjuncture in Africa, fraught with multiple-transitions and troubling antinomies. These include transitions between postcolonial periods and development periods, taking place in an era of renewed conflict as seen in Burundi, Sudan,Somalia, Libya or Egypt or Zimbabwe, and a clear transition from the history of authoritarian political settlements typical of most African countries characterised by limited leadership accountability; to a systematic accountability mechanism for every African country. There is obvious tension here. On one hand the AU is trying to pool sovereignty at the regional level through different high-level political mechanisms, while on the other hand it is contesting accountability at the national level and yet lacks the power to institutionalise checks and balances.

The multi-stakeholder Africa Regional Dialogue, convened by ODIand KIPPRA in April 2016, identified some risks of combining both agendas. Foremost is whether the SDGs and the associated accountability frameworks can help to foster the broader development of national-level accountability. Some African countries may legitimately resist the agreed results framework, citing diversity and complexity of country contexts. It is possible that imposing a regionally agreed framework on countries might be viewed as highly intrusive, and thus open to challenges and resistance. This is not just conjecture – the resistance of some African States (e.g. Uganda,Zimbabwe, Nigeria) to observe the rights of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT) populations despite agreeing to the AU’s 2014resolution 275 on the on the protection against violence and rights violations on the basis of real or imputed sexual orientation or gender identity is a prime example.

At the moment consensus is lacking on how SDG implementation can succeed in environments of disparate governance, especially given the history of failure of most states to aid participatory politics in Africa. The addition of the AA2063 agenda into the global conversation on SDGs offers renewed hope that the AU may have found its political voice. It is yet to be seen, however, whether this newfound voice can gain traction with the AU’s own constitutive bodies and members in a manner that allows the Union not just to bark, but also to bite.

Climate change documentary premiers at Manchester Museum

Last night we teamed up with the Manchester Museum, to premier the documentary ‘The Lived Experience of Climate Change: A Story of One Piece of Land in Dhaka’.

The event was part of the Museum’s Climate Control season, which seeks to not just educate people about climate change, but really engage them in the issues surrounding it. The documentary is a fantastic example of how Dr Joanne Jordan did just that around her research findings on the links between climate change and land tenure in the slums of Dhaka, Bangladesh.

Rather than simply writing up her results in a journal article and perhaps distilling it into a short briefing, Joanne worked with the University of Dhaka to develop her insights into an interactive performance. This was based on a local ‘pot gan’ format and was used to spark engagement and further discussions with the communities living in the slum and with other researchers and policy makers.

Appropriately, the premier was held in the stunning Living World’s galley at the Manchester Museum, adding even more to the drama of the evening.

Working with the talented Bangladeshi filmmaker Ehsan Kabir took a significant investment of time, but it has enabled Joanne to bring the insights of her research to a much broader audience.

Demonstrating the messy complexities of how poverty, migration, gender dynamics and community conflicts interact with day to day impacts of flooding and climate change though drama gives an incredibly rich insight into the experiences of people living in Dhaka’s slums.

Early next year, we’re hoping to present the film in partnership with Bangladeshi organisations in East London … so watch this space!

Staff Spotlight: Dr Joanne Jordan

What is the current focus of your research?

What is the current focus of your research?

My research tries to understand the connections between climate change, vulnerability and complex notions of risk. For the past nine years, I’ve been working on those issues in the context of Bangladesh, currently in Dhaka and previously in more rural settings. All of my research since my PhD has looked at local priorities and realities of climate change, trying to understand how communities perceive climate change, what impact climate change has, how that impact varies between different vulnerable groups within the community, and finally, what are the various response strategies they have developed.

More broadly, I’m trying to answer why people act the way they act. Why do they make particular decisions? So a lot of my work involves having in-depth conversations and using a storytelling approach to try to understand motivations. From there, I’m interested in why the impact and responses are so different – the differential can give us a huge insight into why some people and groups are more vulnerable than others.

Why did you decide to do research at the local level?

I’m passionate about communities! Meeting people in the field is what I enjoy the most. When I’m thinking about a theoretical issue, I can think of a participant who illustrated that issue with their story and it’s not just number 55 in my interview sheet – it’s someone with a name, someone I’ve shared a cup of tea with. The personal connection translates to teaching as well: it helps students understand the theories better because they have something more human to relate to.

Why is it important to study climate change at the local level?

If you look at any given international or national intervention, whether it’s going to be accepted, modified or completely rejected by the locals depends on its fit within their understandings of climate change and their everyday realities. So to create effective climate resilience strategies, it’s crucial to really understand how the community works, which requires a lot of fieldwork and examining gender histories as well as cultural and power dynamics. And this applies to all interventions at the local level, not just those seeking to address climate change.

What frustrates you as a researcher?

Being asked, “do the urban poor in Bangladesh understand what climate change is?” It always shocks me: it implies that they (and urban poor in other developing countries) may not know what climate change is, and that climate change or development experts somehow know better. The slum dwellers I work with in Dhaka may not use the same scientific terminology, but of course they know what climate change is. More broadly, the question frustrates me because it implies that the people suffering from climate change in developing countries have to learn something, when in fact they have so much to teach us, the researchers and experts, about climate change and resilience in their local context. I sometimes feel there has been too much focus on the flow of knowledge from experts into communities and not from communities to experts. One is not more important than the other, and there is a need to consider: how can we better integrate these different forms of knowledge?

What do you like about working as a researcher at GDI?

GDI has given me great flexibility to conduct fieldwork. I’ve been able to go to Bangladesh for three or four months in a year and be in a community every day from 6am to 6pm or even longer. That has given me crucial space to challenge any pre-existing notions or opinions, to immerse myself in the community and be open and reflective, which is key in allowing others to teach you something. Even experts can become entrenched.

How does your work address global inequalities which is one of the University of Manchester’s five research beacons?

Currently, mainstream work on reducing inequality doesn’t take into account the different risks that people face as a result of climate change, so the interventions that are aimed at reducing inequality are likely to be less effective. And inequality affects how people respond to climate change – my research looks at how those responses differ and why, and that can point to what kinds of interventions will help even out the playing field. The majority of those affected by climate change are already poor and are likely to become poorer as a result of climate change.

What research project(s) have been highlights for you?

The Pot Gan, which is not a research project itself, but a traditional Bangladeshi folk performance that I developed in cooperation with the University of Dhaka to explore the findings of my latest research on climate change and land tenure.

It came about because you can have an impact as a researcher if you analyse data, publish papers, disseminate your work and teach students, but I always wanted to go a step further. The Pot Gan is my attempt to give something back to the community I studied rather than parachute in, get my data and run back.

What research is the Pot Gan based on?

My ongoing work on urban climate change resilience and vulnerability. Most of the research is forthcoming, but broadly looks at how climate change and its impact influence land tenure and how land tenure may influence the impact of climate change.

It’s fascinating to me how climate change is so closely linked to other risks the urban poor face: imagine you are renting a house in a slum in Dhaka for £20 per month. The landlord decides to undertake a really positive intervention: upgrading the house to make it more resistant to climate change, namely flooding. Your rent may go up to £25-30. That might only sound like a few pints in the pub for us, but in Dhaka it may mean that the renter can no longer afford to live in that house and has to move to other housing that is even more prone to flooding. Or they endure the rent increase, but that exacerbates a different vulnerability by raising the economic pressures they are under. The intervention was positive and lowered one risk, but the renter either hasn’t escaped it at all, or has found another risk is increased.

If I went to visit Dhaka, what’s the one thing I should do or see?

My best days in Dhaka have always involved getting up at sunrise armed with my camera and wandering around the streets in Old Dhaka: the most captivating thing about Dhaka is simply watching life unfold in front of you. You don’t have to look hard! Everyone should definitely go on a walking tour with the Urban Study Group; they are a nonprofit organisation campaigning for the conservation of architectural heritage in Old Dhaka. I’d also take you to a restaurant in the slum I work in; I think it makes the best singara in all of Dhaka and a few streets down you can get the most amazing fresh coconut water! In the evening I’d recommend Jatra Biroti for some live folk music and amazing vegetarian food.

Alumni profile: Juan M. Villa

Juan, originally from Colombia, completed his PhD in Development Policy and Management at GDI last year and is now living and working as an economist in Washington DC. He has also provided consultancy on a number of international poverty and economics projects, for organisations including the United Nations Development Programme, United Nations University and UNICEF.

Juan, originally from Colombia, completed his PhD in Development Policy and Management at GDI last year and is now living and working as an economist in Washington DC. He has also provided consultancy on a number of international poverty and economics projects, for organisations including the United Nations Development Programme, United Nations University and UNICEF.

What was it like to study in Manchester?

As an economist, my best memories orbit around the exploration of an amazing city that has changed the world. Being able to recreate the roots of the industrial revolution at the Museum of Science and Industry, visit the Cheetham Library where Karl Marx would discuss the first relationships between the proletariat and bourgeoisie. The great achievements of Richard Cobden in the field of free trade were very inspiring. The University of Manchester has also witnessed a broad global progress, being the birthplace of the first programmed computer, the workplace of Alan Turing and home of graphene.

Why did you choose to study at GDI?

I met Professor Armando Barrientos who was working on topics related to my research preferences. He encouraged me to come to GDI (then Brooks World Poverty Institute) to start my PhD research on the exit conditions of participants in antipoverty transfer programmes. All this combined with the fact that GDI is a world class research centre with wide recognition in academic fields and multilateral agencies made it an easy choice. And I was grateful to receive the Bouldin Scholarship for my doctoral studies, funded by University of Manchester alumnus John Bouldin and his wife Elizabeth.

How did you pick your research topic?

I was working on the evaluation of antipoverty transfer programmes in Colombia. Despite my strong empirical focus, I had an academic interest in conceptualising what I was looking at in the field and to test other hypotheses to help antipoverty programmes achieve better results.

It’s only been a year but what have you done since graduating?

Just before my viva I found a research position in Washington DC at the Inter-American Development Bank, which is the most important development agency in Latin America and the Caribbean. I am now a research fellow in the labour markets and social security division.

Has your University of Manchester qualification helped you in your professional life?

Yes. During my PhD I was able to understand the global and specific contexts of antipoverty policies in developing countries. This ability has strongly helped me in the design and implementation of antipoverty transfer programmes in Latin-America, the Caribbean and some African countries.

Do you have any tips or advice for current students, particularly those who are about to graduate, for life after Manchester?

For those pursuing PhDs: your research does not end with your viva or after graduation. I still have GDI in my heart and I keep doing research with my PhD supervisor. I’ve also contributed to the GDI Working Paper Series and was appointed as an Honorary Research Fellow of the GDI.

Do you want to know how poor people really manage their money?

Professor David Hulme, Executive Director, Global Development Institute

Back in 1999 the Institute for Development Policy and Management started working with Stuart Rutherford (now an Honorary Research Fellow at the Global Development Institute) on a research project to deepen our understanding of the ‘poor and their money’.

I had learned a lot from my work with Paul Mosley on ‘Finance Against Poverty’ but I had realised that one wave or two wave surveys did not capture the sophistication of poor and low-income people’s financial lives. It was evident that the dominant narrative of the 1990s –‘poor people need micro-credit’ – was flawed. It was also clear that most research on microfinance (especially by economists) failed to cover informal financial services which, even in microfinance-saturated Bangladesh, were the larger part of poor people’s financial activities.

What to do came to me on a late night train taking me home to Wilmslow after a day in London – DIARIES! Well, actually not strictly ‘diaries’ but fortnightly reports from skilled research assistants over a 12 month period, to record all the financial services (formal and informal) that 50 households in Bangladesh and 50 households in India used. Stuart and I recruited Orlanda Ruthven and, with a Department for International Development research grant, started the work that culminated in the microfinance bestseller book ‘Portfolios of the Poor’.

This revealed that poor and low income people weave together dynamic portfolios of formal and informal financial services (just like you and I) to meet their changing needs and circumstances. It showed that poor/low income people needed flexible financial products and that savings services are as important as loans. Take a read of the book – it’s excellent.

Being a ‘bad academic’ I moved on to researching other issues. But Stuart, who claims to be a ‘non-academic’, stuck to the poor and their money. With colleagues he has deepened and refined the ‘diaries’ methodology so that data is collected on a daily basis.

- Details of the up to date methodology for the Hrishi diaries for CGAP

- The latest report on their findings (Interim Report V2)

- The Hrishipara Daily Diaries website

This is an extraordinary resource – a blow-by-blow account of the daily financial lives of 50 poor/low income households in Bangladesh. It covers their trials and tribulations (coping with deaths in the family and court cases) and successes (successful microenterprise initiatives and weddings). It covers the way they use microfinance institutions (MFIs) and their rich, informal financial lives. If you have not got 12 months to sit down in a village in Bangladesh and talk with low income/poor people then these latest diaries are an amazing shortcut to uncovering the insights that high quality fieldwork provides… and they are also an enjoyable read. Do not miss them.

Moving up the ladder: How does India do in social mobility?

By Kunal Sen, Professor Of Development Economics & Policy, Global Development Institute

By Kunal Sen, Professor Of Development Economics & Policy, Global Development Institute

A question of long-standing interest among social scientists is the degree to which an individual’s status in society is determined by the position of one’s parents. In egalitarian societies, where you are in the social and economic status ladder should not be principally determined by your parent’s income, educational level or occupation. Social mobility research has been concerned with intergenerational occupational mobility, but much of this research has concentrated on advanced market economies. However, this question is of crucial importance in the developing world, and especially in emerging economies which have undergone modernisation as they have opened up to the world economy in recent decades.

Together with my co-authors Vegard Iversen and Anirudh Krishna, I look at this question in the context of India, a country which has witnessed rapid economic, political and social change since the 1980s. Using a nationally representative data-set – the Indian Human Development Survey of 2011-2012, which has detailed information on the occupations of fathers and sons, we find a relatively high degree of social mobility among urban residents in India, with around 26 per cent of sons whose fathers were in the lowest occupational class – construction workers and other labourers able to achieve the highest two occupational classes – clerical workers and professionals. However, the degree of social mobility is far lower in rural India – only around 10 per cent of the sons of fathers in the lowest occupational class could achieve the highest two occupational classes.

More disturbingly, we find significant differences in social mobility by social group in India – Dalits (or Scheduled Castes) and Adivasis (or Scheduled Tribes) are the most disadvantaged social groups in India, with high rates of poverty, and these two social groups see very low rates of social mobility as compared to forward castes in India. For instance, only 11 per cent of Dalits and 9 per cent of Adivasis whose fathers were in the lowest occupational class could achieve the highest two occupational classes, while 25 per cent of forward caste individuals could. This suggests that barriers to occupational mobility still persist in India’s most disadvantaged social groups in spite of widespread affirmative action programmes and intense political mobilisation of these groups since independence.

We also find that for India’s historically disadvantaged communities, the high risk of a sharp descent in the occupational ladder, where the son ends up in the lowest occupational class when the father is in the highest two occupational classes, is between 3.5 and 4 times higher than it was in Victorian Britain. In contrast, for a forward caste son residing in urban India, the sharp descent risk is on par with the corresponding risk in Victorian Britain. Finally, we find striking parallels between upward mobility prospects and sharp descent risks in India and China, two societies which differ greatly in terms of their social and political structures as well as their rates of economic and social development. Reversing these trends in the world’s two most populous countries is essential for greater equality of opportunity and a fairer society in China and India.

David Hulme looks ahead to the DSA Conference in September

David Hulme, Executive Director, Global Development Institute

I am just back from Japan – a delightful visit with colleagues in Nagoya and Tokyo. The only cloud, in a very sunny week, was hearing about the scale of public support for a populist, nationalist right-wing party in Japan. Does this sound all too familiar…the UK, France, the Netherlands, Austria…and over to Donald Trump in the US? Our theme at the DSA Annual Conference is ‘Politics in Development’. Much of the agenda is about the politics of developing and emerging countries, but we shall have to allocate time to asking about what is happening to ‘politics’ in the rich world – as it has very big implications for international development and increasingly these seem to be turning negative.

This year’s conference is all set to be a very productive three days. Its sessions look at the big issues and challenges of international development and, alongside these, at detailed work on theoretical, methodological and applied topics. Outside of the sessions there are great opportunities for informal discussions in Oxford’s many cloisters, cafes and bars.

But, what a difference a year makes! Last year at the Development Studies Association 2015 conference at Bath there was an air of cautious optimism about the global context for making the world a somewhat fairer place and tackling poverty and inequality. The Sustainable Development Goals were about to be unveiled in New York – very long, and very long-winded but reflecting deep discussions by all UN member states: a real step forward for global democratic deliberations. Arrangements for the Climate Change talks in Paris were making good progress according to the ‘sherpas’ setting up the negotiations. Europe was having problems with ‘migrants’, but Angela Merkel was encouraging EU governments to fully honour their UN commitments to supporting refugees and helping migrants.

In mid-2016 things look very different and an air of deep pessimism and/or profound precariousness is evident. For those of us who are UK citizens (and especially for people working in universities) the Brexit vote means that the future is very unclear. Isolationism, protectionism and xenophobia seem to be the values that are sweeping around the UK…and Europe…and further afield. For many involved in teaching and research on international development the public popularity of such values, and associated policies, challenges many of the values that have underpinned the promotion of development – international cooperation, economic and social integration, welcoming people from other parts of the world, global social justice and human rights.

But, we need to rise to this challenge…and perhaps take some responsibility for it. Have we, as academics, teachers and researchers, focussed our work on those who think like us and neglected our role as contributors to ‘public understanding’? Could we have done more…and can we do more in the future…to help our fellow citizens and people in other countries understand that in the 21st Century we all live in one world. If we want an international environment that is stable, prosperous and sustainable for ourselves and for future generations then, as Angus Deaton writes, we (humanity) “are all in this together”.

There will be lots of opportunities to discuss our detailed work at the Conference and also to think about what DSA members and DSA as an organisation can do to help public understanding in the UK of the need for collaboration and cooperation between people and countries. Please do some thinking in advance and come prepared – what can we in DSA (as individuals and as an organisation) do to make Brexit less damaging for international development?

Could you also put a little thinking into ‘whom’ you would like to elect to DSA Council to represent your views? There will be several positions coming vacant this year and we need energetic and committed members to join the Council. Please send nominations to our Secretary, Fiona Nunan before the Conference.

The Power Dynamics of Big and Open Data

Richard Heeks, Professor of Development Informatics, Global Development Institute

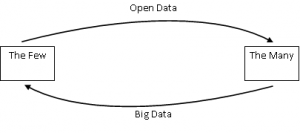

At a recent CDI brown-bag discussion on data-intensive development, we hypothesised a mirror-image power dynamic between big data and open data.

Open data has an inherent tendency to redistribute power from the few (who originally hold the data) to the many (who can now access the data). It supports sousveillance. Big data has an inherent tendency in the opposite direction. It gathers data about the many but only the few have the power to capture, store, process, interpret and use that big data. It supports surveillance.

The extent to which these are inherent affordances of these data systems vs. the extent to which these tendencies are inscribed into those data systems is a matter for further debate. But what it does suggest is that big data per se is more reproductive than transformative of power inequalities within society. Think of the way in which major users of big data – social media platforms, e-business multinationals, telecommunication companies – operate. Their uses of big data reinforce inequality much more than they challenge it.

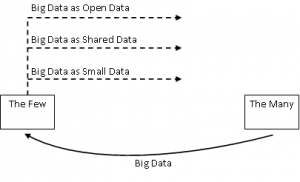

One way to address this is to reverse the power dynamic flow shown above: big data must become open data. This could happen in various ways:

- Big data as open data: big datasets are made openly available online in accessible format (as in all cases, with due consideration for data privacy and security).

- Big data as shared data: big datasets are made available to particular organisations (e.g. those of civil society).

- Big data as small data: sub-sets of big datasets are shared with the sources of that data for their use (e.g. the particular communities or groups from which the big data derived).

But what will make a reversal happen? To understand this, we need to study open data motivations: what causes organisations to open their datasets? Reviewing our knowledge of open data, we could not find examples of intrinsic motivations driving adoption of open data. Instead, drivers to opening of big datasets seem likely to be extrinsic:

- For public sector owners of big data, domestic political economy (e.g. local campaigns for access to data; economic benefits from creation of a local data economy) and external political economy (e.g. encouraging foreign investment through a reputation for openness).

- For private sector owners of big data, government regulation to force opening of datasets, or shareholder/consumer pressure.

Without such extrinsic pressures and the openness that ensues, big data may not deliver its developmental potential.