Dr Judith Krauss, Lecturer in Environment and Climate Change

Can I ask you a question? Do you like chocolate? If your answer is ‘yes’, as for 100% of my focus-group and public-engagement participants, you may be interested to know that the people manufacturing your favourite treats are not entirely sure where your fix’s key ingredient will come from four years from now.

Can I ask you a question? Do you like chocolate? If your answer is ‘yes’, as for 100% of my focus-group and public-engagement participants, you may be interested to know that the people manufacturing your favourite treats are not entirely sure where your fix’s key ingredient will come from four years from now.

Six years ago, projections that cocoa demand would outstrip supply by about 25% by 2020 began circulating. Factors contributing to the shortage concerns include: cocoa cultivation’s lacking attractiveness for younger generations given decades of low prices, productivity-maximising practices degrading limited production surfaces and the unknown variable of climate change, as well as only a handful of companies controlling the marketplace. The impending doom has prompted the chocolate sector to begin engaging with ‘cocoa sustainability’ to address these issues and safeguard its key ingredient’s long-term availability.

The bad news: nobody quite knows how to do that.

The good news: chocolate-industry actors have begun engaging in various fora and initiatives to address a problem together which is too monumental for any one stakeholder to tackle alone. One such forum, bringing together diverse chocolate-industry actors from civil society, public sector and private sector, is the World Cocoa Conference (WCC), taking place in the Dominican Republic from 22 to 25 May 2016. Stakeholders from all facets of the cocoa sector have congregated to discuss ‘Building bridges between producers and consumers’, with a view to ‘connecting the whole of the value chain’.

My PhD research sought to do just that, using a global production networks lens to incorporate voices from cocoa producers via companies, public sector and NGOs to chocolate consumers. Through in-depth interviews and participant observation in Latin America, I aimed to find out what cocoa producers, cooperatives and NGOs make of ‘cocoa sustainability’. Back in Europe, I sought to establish companies’, public-sector representatives’ and consumers’ take on the omnipresent term. In keeping with the WCC’s theme of building South-North bridges, I fed back through interviews, focus groups and public engagement what I had learned especially from Nicaraguan stakeholders.

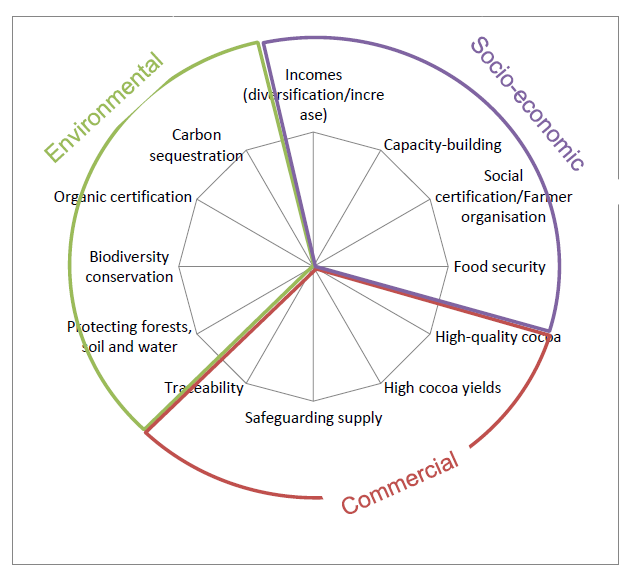

Regarding the ‘cocoa sustainability’ challenge, my research produced some more good news and some more bad news. The bad news first: a key difficulty with the concept of ‘cocoa sustainability’ is that various actors bring different understandings of what it is or is to entail to the table. This polysemy on the one hand works in the concept’s favour, as its aspirational quality renders it a notion which diverse stakeholders happily agree on. However, it also paints over different framings of what ‘sustainability’ is to entail: some prioritise its potential to improve grower livelihoods through better prices and cultivation conditions, others emphasise its links to global environmental challenges; a third dimension concerns predominantly commercial concerns such as supply security, i.e. the business imperative which ‘sustainability’ has become in the sector.

The good news is, however, that because of cocoa stakeholders’ puzzlement at how to bring about ‘cocoa sustainability’, they are willing to rethink time-honoured processes and procedures. I believe this awareness is an opportunity to create genuine, fair partnerships between stakeholders throughout the supply chain. One avenue to get closer to some equitable conversations, I believe, could be the ‘constellations of priorities’ model which I developed in my work, a tool to (self-)assess stakeholder priorities so that all actors within an initiative can identify where their socio-economic, environmental and commercial drivers overlap, dovetail or collide.

My hope is that the model can help practitioners and researchers identify synergies and tensions, as some priorities are likely to be incommensurable, but many can be made more compatible through equitable engagement (cf. my website; podcasts, slides and reports in English, Spanish and German available as a thank-you to stakeholders).

My hope is that the model can help practitioners and researchers identify synergies and tensions, as some priorities are likely to be incommensurable, but many can be made more compatible through equitable engagement (cf. my website; podcasts, slides and reports in English, Spanish and German available as a thank-you to stakeholders).

More bad news emerging from my work: despite actors’ growing awareness, answers in the transformational spirit required by the challenges’ magnitude are mostly still in their infancy. In public-facing representations communicating to consumers initiatives’ meanings, stakeholders often forefront socio-economic and environmental objectives as the driver of their engagement. While purporting to ‘build bridges’ and playing into consumers’ desire to ‘help’, the charitable meanings created also paint initiatives as ‘nice-to-have’. This altruistic canvas hides from view the poor practices, incentivised by low prices and productivity-maximising pressures, which partly have brought about the current crisis. What is more, unbeknownst to consumers, initiatives can exacerbate the power asymmetries they purport to bridge between especially cocoa producers and chocolate companies. Through companies establishing certification schemes they oversee themselves and working directly with producers, they cut out intermediaries. While this approach can, much to growers’ delight, increase farm-gate prices, it also exacerbates corporate dominance and creates quasi-monopsonistic structures, leaving producers with few or no other sales outlets.

In my view, more equitable connections are crucial to tap into Southern stakeholders’ expertise through genuine participation and empowerment and transform the sector towards greater viability. While certification schemes such as Fairtrade or organic can offer part of the answer and reduce the likelihood of infractions vis-à-vis most uncertified chocolate, ever more stakeholders agree they have to move beyond. I would argue that supporting smaller-scale cocoa processing and chocolate production in the global South could help promote greater value capture at origin, more viable practices and broader genetic diversity– Nicaraguan chocolate proved a particular favourite for my focus-group and public-engagement participants. To build genuine consumer-producer bridges, conduct prioritising equity and fairness, towards humans and the environment, would indeed be a principle worth applying in cocoa, but also far beyond.

It is up to you what you make of all this good and bad news, whether you opt to order industrial volumes of your favourite chocolate, figure out how to shock-freeze chocolate and then buy a bigger freezer, or choose another route. It is up to consumers, with the limited power of their purse-strings, and chocolate stakeholders, with the virtually unlimited power of their production-network tentacles, to make the informed, transformational choices necessary to help ‘save our chocolate’: living incomes for Southern stakeholders, production practices which protect rather than destroy the environment, and interactions in a spirit of equity and fairness rather than charity.

However, in light of the crisis, I would advise you to take to heart two fundamental truths which have made my PhD – aka thinking about chocolate 24 hours a day, seven days a week for three years – infinitely more enjoyable:

– Chocolate is proof that God wants us to be happy.

– Chocolate comes from cocoa, which grows on a tree. That makes it a plant. Therefore, chocolate is practically salad. Eat up!

This blog originally appeared in May 23, 2016

Find out more about our Master’s courses

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole