Students on the MSc International Development programme travel to Uganda each year to conduct relevant research projects:

In the first of three posts by students, Laura Dempsy reflects upon the difficulties Uganda is facing in its battle to eliminate mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS.

By Laura Dempsey

The population in Uganda is booming and I was constantly reminded of this during a recent research trip out to the country. Commissioners in the Capital spoke, arguably over, enthusiastically about policies designed to target the growing number of youth and members of a small rural village told of tradition requiring them to continue birthing children until they produced a son.

Subsequently the average Ugandan woman births 6 or more children in her lifetime. Couple this with the county’s recent increase in new cases of HIV/AIDS and it becomes clear that the prevention of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS, or as the new programme announced mid-march significantly re-terms it- the elimination of mother to child transmission of HIV/AIDS (EMTCT), remains an important issue to be tackled by Uganda.

A 10 day stay in Uganda brings me to reflect on why the nation is still tackling this form of transmission of HIV/AIDS. Why are women not utilising the EMTCT services? When facing passing a life threatening disease onto your offspring, what factors are preventing women from taking necessary action to prevent transmission? The following reflection is drawn from meetings, interviews and discussions with Ugandan’s in various national ministries, non-governmental organisations and lastly, and arguably most vitally, local, every day Ugandans. Subsequently I must disclose that the following discussion has severe research limitations and is relevant only to the specific districts and groups in which I collected the information. Before I left for Uganda I wrote a piece analysing the barriers and drivers influencing the use of EMTCT services within the country framed by the Health Belief Model and as such this reflection will also use this same lens (Janz & Becker, 1984). I previously discussed a wide range of perceived barriers and benefits but I will focus on the most noteworthy that I witnessed during the trip.

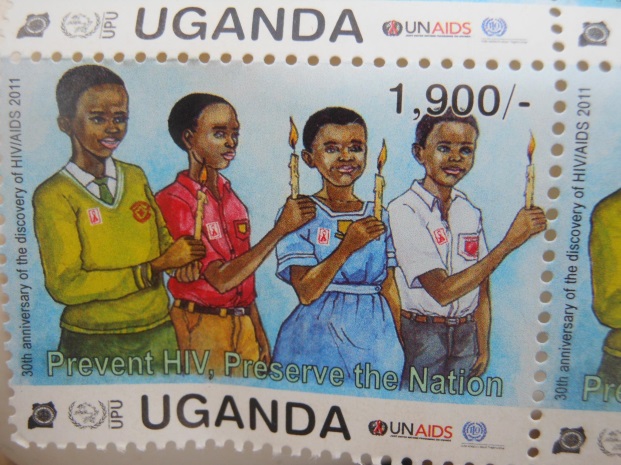

HIV prevention message on Ugandan stamps

Tied to potential renewed stigmatisation due to the HIV and AIDS Prevention and Control Act that was signed into law in 2014 , the most prominent barrier to women making use of EMTCT services is the grave gender inequality present throughout Uganda, reconfirming what I had previously read. Rural women speak of males as ‘bosses’, whom even as early as seven years old refuse to help their mothers as they take their place in the heavily patriarchal society.

In Buliisa many men assign themselves to a life of fishing and drinking as their female counterparts farm and provide for the household, observing first-hand how schools send only female students to collect water in jerry cans, leaving their male counterparts in class. Even in urban Kampala, one university educated female, spoke of the gendered domestic expectations that society already has destined for her and the shocking rates of rapes of young girls and tales of prostitution further highlight women’s inferior status in Ugandan society.

HIV prevention message at Buliisa school

Particularly in rural Uganda this over-reliance on women to provide for the household, means that many simply don’t have the time to attend antenatal care, as literature on competing demands of women had previously suggested, with some working in their fields until their labour begins. This gender inequality also prevails in concrete and traditional gender roles in Ugandan society. There is a social requirement for men to be ‘strong’, unexpected to seek medical help until it is a fatal matter, contrasting sharply and unproductively with how I found certain EMTCT clinics to operate, reducing utilisation of services.

Previously I had discussed the successes of male involvement in other African countries and concluded this could be the way to encourage women to utilise EMTCT, yet the reality that greeted me in Uganda illustrates the complexities of drawing men into the EMTCT process. Many hospitals and health clinics offer HIV/AIDS couples testing and some withhold results until partners attended clinic with the pregnant women.

Despite these good intentions, rather than reducing perceived barriers faced by pregnant women, such practice has instead created new barriers. A nurse at Buliisa’s level 5 hospital contributed the current phenomenon of women bringing in random men, in some cases paying BodaBoda (motorbike) drivers to act as their ‘husbands’ to obligatory couple testing.

A couples testing sign outside a clinic in Buliisa District

The Aids Support Organisation (TASO) has recognised this bad practice and instead of enforcing tests has designed incentives to encourage couples testing. Couples are offered meals while at the clinic or are seen quicker by health workers to challenge the barriers of lack of time and the necessity to provide for their families that prevent males from accompanying their pregnant wives to clinic. Such practices though may disproportionately disadvantage women with unplanned and teenage pregnancies. These women could be further discouraged from using EMTCT services when the father of the child is unknown or unable to attend clinic, a common occurrence in rural areas with high prostitution and numbers of early pregnancies.

Another barrier to EMTCT, previously suggested by literature – the distance women had to travel to EMTCT clinics does appear apparent in rural Buliisa. Yet what has stronger influence was the lack of perceived benefits of seeking EMTCT treatment, by the rural population. Buliisa has, off the back of Tallow Oil Company’s corporate social responsibility scheme, been built a hospital, but after visiting it the failings in health services are clear as cited in literature. There was only one Doctor on the staff list, most of the wards were barren of furniture and any equipment the hospital did have was piled up, unused. The administrator at the hospital told of a lack of drugs as they were yet to be allocated a budget for medication and instead were ‘sharing’ drugs with a clinic in the town.

Focus group: Buliisa village

Employees of TASO reconfirmed these problems as they discussed a lack of human resources, medication and equipment stock outs as major problems in EMTCT implementation for many clinics. In some regions there is one midwife

Uganda is attempting to solve its staffing problems with the Ministry of Health offering scholarships to nurses who want to specialise in midwifery, with a commitment that on qualification they will work in rural areas, such as Buliisa where human resource lacking are more prevalent, yet they must also evaluate wages to ensure these trainees aren’t poached by countries such as South Sudan and South Africa, whom offer competitive benefits to midwives. Uganda is facing a ‘brain drain’ of its trained medical staff to surrounding and higher paying countries .

Reminiscent of resource lacking’s throughout the country TASO employees informed me of one case in Jinja where a Doctor had refused to deliver a baby as the clinic had no surgical gloves, instead referring the mother to another health facility who subsequently died en route. Such stories coupled with a widespread presence of bribing medical staff for treatment results in the perceived benefits of attending EMTCT clinics being precariously low for Ugandan women. Why go to the effort of seeking EMTCT when the treatment provided is below standard anyway from under-educated and low numbers of staff, especially when Uganda’s current policy on HIV/AIDS requires mothers to be on ARV’s for life -a difficult ask during stock outs.

It seems the government has a lot more responsibility than I had previously suggested in tackling EMTCT. Yes, structural inequalities deter women from accessing EMTCT services, but alongside challenging these, the budget for health needs to be increased to enable successful implementation of EMTCT polices. The complexities and multi-dimensional barriers to EMTCT though means that just increasing the budget would only be one part of the puzzle for successful EMTCT.

The poor in Uganda speak of hunger killing them today, with AIDS a distant threat of coming years and so through utilisation of the health belief model it is easy to see how the perceived benefits of engaging in sex-work and avoiding attending PMTCT outweigh the barriers, ensuring themselves and their families can survive the day.

Although Uganda’s and its NGO’s efforts to involve men in EMTCT services to control the spread of HIV/AIDS should be congratulated for its good intentions they need to review the effects this is having at household level. A programme designed specifically for young mothers and sex workers, if implemented correctly could also make some progress in achieving EMTCT as there doesn’t appear to be any real focus on these mothers in EMTCT services at present and they are already facing so many barriers to treatment.