Since May 2015 we have been recording the daily money transactions of up to 70 households living near a small market town in central Bangladesh. These ‘daily financial diaries’ shed light on the money-management behaviour of low-income households, described in papers which can be found on the project’s website. Up to now we have explored matters that face all our ‘diarists’, such as savings and credit, income and expenditure, health, and education.

‘Tracking transactions, understanding lives’ is a new series focusing on individual diarists. We aim to create vivid pictures that give readers a sense of what these lives are like. We hope this will help researchers and activists design better interventions for low-income households.

Radhu

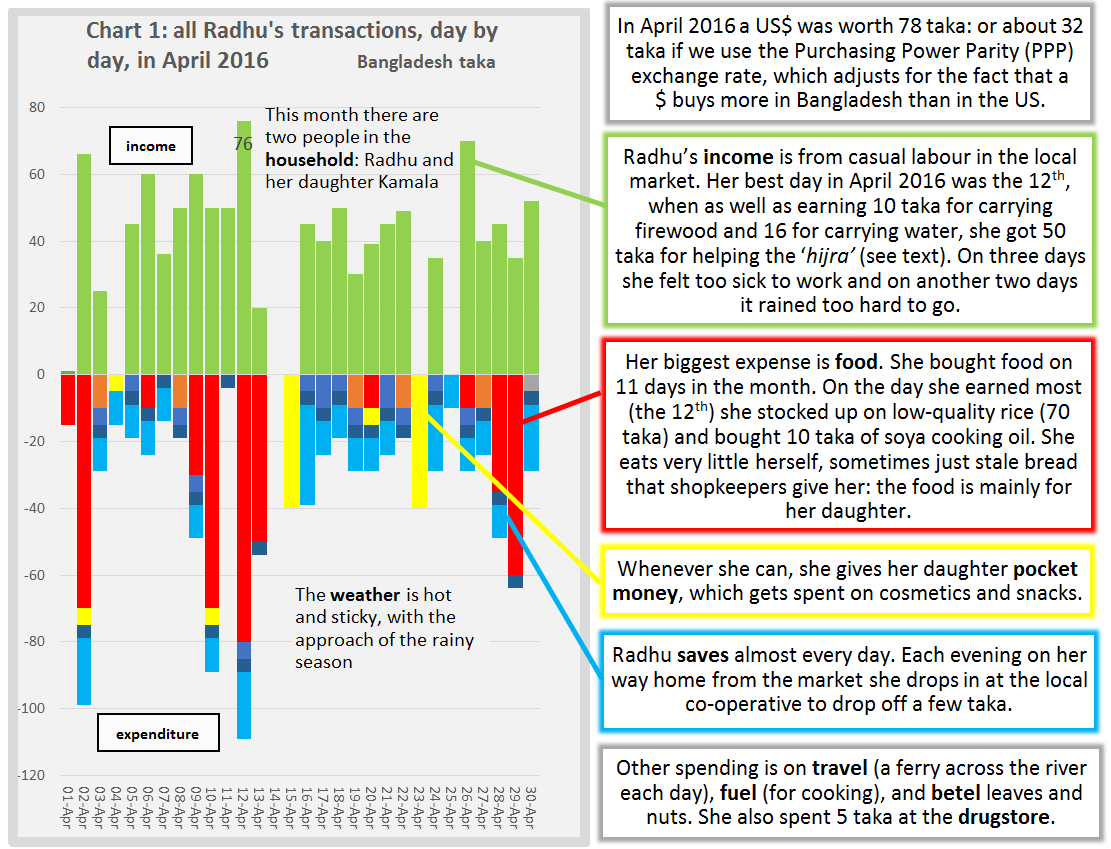

This first posting is about Radhu (not her real name), one of our poorest diarists, whom we have tracked since late May 2015. We get a first glimpse of her life from Chart 1. It shows her transactions during April 2016, a month when her household consisted of two people – herself and her teen-age daughter Kamala. The horizontal axis forms the timeline, with income and expenditure categories distinguished by colour, and measured in Bangladesh taka on the vertical axis.

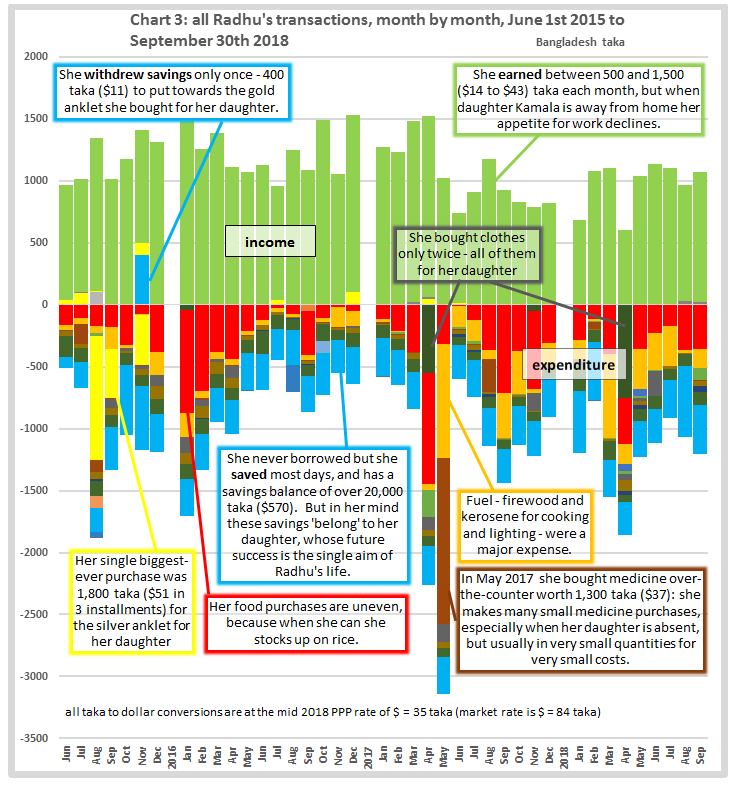

Her earnings in the month totalled 1,113 taka (PPP$34.78), of which she spent 770 taka and saved the rest. That means that Radhu and Kamala lived on an income of 60 cents PPP per person per day that month. That is extremely low, and is a reason why Kamala soon began to spend more time living with relatives elsewhere. If we look at Radhu’s income over the full three and a half years we have known her, her ‘per-person-per-day’ income averages out at just under PPP$1. Even that is still very low: the World Bank and others consider any income less than PPP$1.90 a day as ‘extreme poverty’.

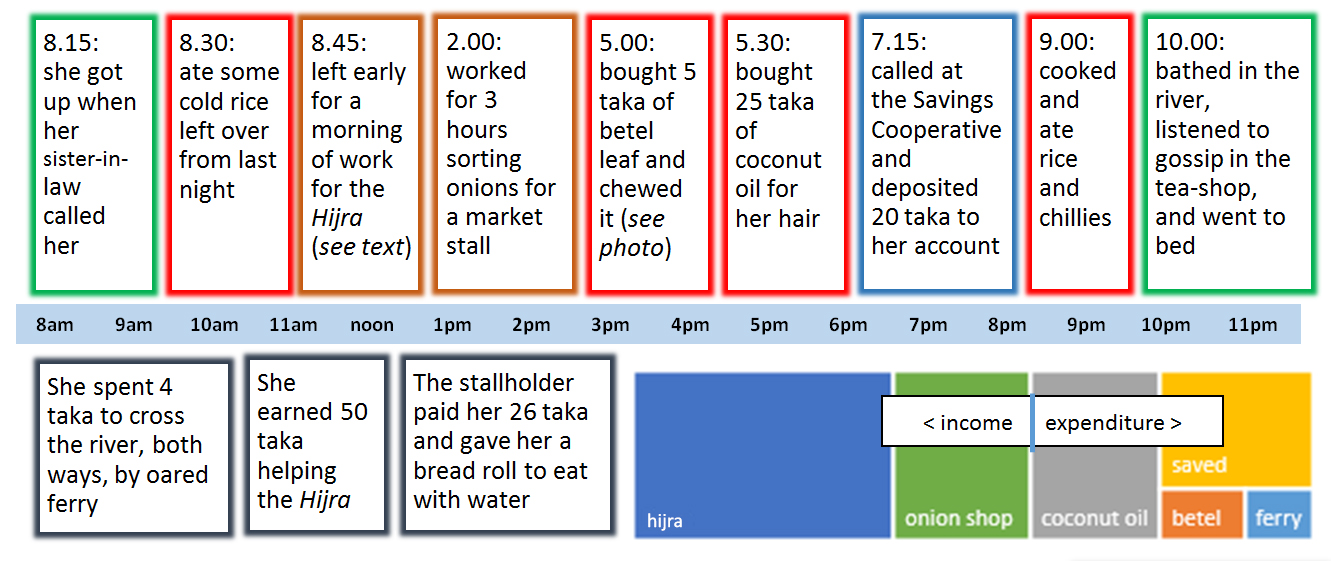

Next, in Chart 2, we narrow the timeline and look at how she spent a single day – 29th September 2018. By this time she was on her own – daughter Kamala was living with cousins.

The Hijra, male-to-female transgender folk who survive by accepting gifts from market stallholders in return for not disrupting the market, are usually there on Tuesdays and Saturdays, and pay Radhu for helping them load their ‘gifts’ into their rickshaw. It’s her best-paid job, and she rewards herself with coconut oil for her hair, which she puts on after bathing in the river (she bathes once or twice a week). Radhu doesn’t set time aside each day to pray: though she’s a believing Hindu, her religious activities are limited to attending the biggest festivals and the occasional kirton, or religious meeting.

The Hijra, male-to-female transgender folk who survive by accepting gifts from market stallholders in return for not disrupting the market, are usually there on Tuesdays and Saturdays, and pay Radhu for helping them load their ‘gifts’ into their rickshaw. It’s her best-paid job, and she rewards herself with coconut oil for her hair, which she puts on after bathing in the river (she bathes once or twice a week). Radhu doesn’t set time aside each day to pray: though she’s a believing Hindu, her religious activities are limited to attending the biggest festivals and the occasional kirton, or religious meeting.

Radhu is in her late forties and a widow. She is from a very poor family and was twice pushed into marriage against her will by brothers who believed she was a drain on the household’s resources. She ran away from the first husband when she found he was already married, and her daughter is by her second husband, an old man who died soon after the child was born. He had no home of his own, and as a condition of the marriage he built a tiny tin-sheet lean-to onto the side of the family home. Radhu lives there still (photo). It is unfurnished, and leaky.

As a child she had no interest in school, which she never attended, and preferred to help her mother around the house. That much-loved mother died when her sari caught fire and Radhu, the only witness, was unable to save her. She still has nightmares about it.

Radhu’s daughter, Kamala, is now 16. Radhu has reluctantly accepted an invitation to send Kamala to live with cousins in a distant town where she does housework in return for her keep. This, it is hoped, will improve Kamala’s chances of marrying, but no suitor has yet come forward. Kamala’s absence is distressing for Radhu, who misses her daughter dreadfully.

The importance of Kamala in her mother’s life can be traced in Radhu’s transaction record, as seen in the final chart where we show her transactions each month for more than three years.

Although she is widowed and very poor, Radhu gets no regular state welfare payments, partly because she is easily overlooked, partly because it is local leaders who recommend candidates for benefits to the local authority and her family belongs to the ‘wrong’ religious faction in the village. But a change in local authority leadership means she can now buy the low-quality highly-subsidised rice that the government occasionally makes available.

In an income satisfaction survey we ran, Radhu reported that “I cannot eat three meals properly and cannot provide many things that my daughter needs”. She doesn’t think her situation is likely to change, and clings only to the hope that her daughter’s life will be better than her own.

Stuart Rutherford

Hrishipara, Bangladesh, November 2018

The Hrishipara Financial Diaries Project is currently being funded by the UNCDF SHIFT Programme based in Dhaka Bangladesh, and we are grateful for their support.

The Hrishipara Financial Diaries Project is currently being funded by the UNCDF SHIFT Programme based in Dhaka Bangladesh, and we are grateful for their support.

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- What the poor spend on health care?

- How the poor borrow?

- What do poor households spend their money on?

- Tracking the savings of poor households

- When poor households spend big

- When poor households spend big part 2

- Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

- Receiving Gifts in Low-Income Households