The story so far

The first blog in this series was written just after a ‘corona lockdown’ was enforced in Bangladesh on 26th March 2020. It discussed the reaction to the shock of the 60 low-income households in central Bangladesh who volunteer as ‘diarists’ in our daily financial diary project. The second blog showed how bad things got during April, the first full month under lockdown. The third blog reviewed the partial recovery that took place in May and wondered if the ending of the lockdown on 31st May was a good idea. This fourth blog notes a partial recovery in economic and financial life in June, set against a surge in Covid-19 cases and deaths in Bangladesh.

By May 31st, the day the national lockdown was lifted in Bangladesh, the country had recorded 47,153 confirmed cases of the disease and 650 deaths. But the curve had just begun to rise rapidly and by the end of June had reached 145,483 cases and 1,847 deaths. Record numbers of new daily infections and deaths occurred in the last week of June. These trends are continuing as July starts.

Of our sixty volunteer Diary households, only one has been directly touched by the disease, and the couple involved have recovered. They were among a cluster of cases at the local government hospital where they both work. The research area has not been among the most severely affected, though there have been several cases of deaths of people with corona-like symptoms but who received no treatment and were not officially confirmed as infected. They died at home, since hospitals and clinics have proved unwilling to accept people suspected of having the disease.

Against this background, local people, including our diarists, have come out onto the streets again, resumed some of their normal economic activities, and started borrowing and saving again. We look first at what has happened to the households that we featured in our earlier blogs.

Liaqat

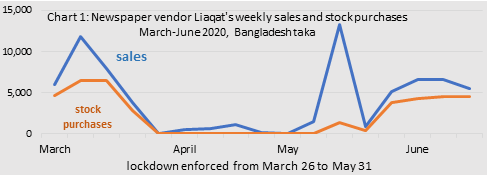

We met newspaper vendor Liaqat in the first blog when we reported on the total collapse of his business immediately after the lockdown began. Chart 1 shows developments since then.

As soon as the lockdown was lifted two things happened: street sales to casual customers resumed, and Liaqat was able to visit credit-customers to collect payments due. As a result that week his income rose above his long-term average. Since then he has resumed daily stock purchases, but at a lower level (670 taka a day) than before the lockdown (930 a day), so he is still suffering an overall fall in business of about one-third. He has had no alternative cash income whatsoever, but has grown some quick-maturing vegetables on his patch of land and has tended his cow, which is in milk.

Samarth

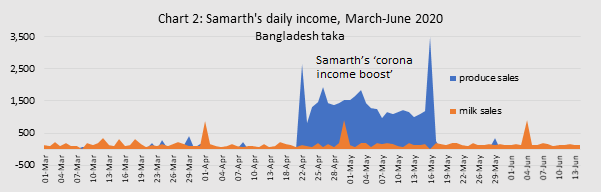

Samarth featured in the second blog, which covered April. He is an entrepreneurial type with a finger in several pies, but his greatest love is for his cows which he both milks and raises for sale. Milk sales comprise his most common income source, and usually bring in enough to keep the family fed and clothed. During April he spotted an opportunity to sell vegetables and spices on the street given that the pandemic made it hard for his neighbours to go and buy at the local markets. Some of the items came from his land, but most were bought locally from farmers unable to reach wholesalers because transport was disrupted.

Samarth featured in the second blog, which covered April. He is an entrepreneurial type with a finger in several pies, but his greatest love is for his cows which he both milks and raises for sale. Milk sales comprise his most common income source, and usually bring in enough to keep the family fed and clothed. During April he spotted an opportunity to sell vegetables and spices on the street given that the pandemic made it hard for his neighbours to go and buy at the local markets. Some of the items came from his land, but most were bought locally from farmers unable to reach wholesalers because transport was disrupted.

As the second chart shows, this considerably boosted his daily income for about a month.

But by the second week of May rumours that the government was likely to relax the lockdown meant that his street sales started to decline. He was bored with the ‘shop’ and wanted to get back to looking after his cows. On 16th May he sold his remaining stock and ended the experiment. He had kept his underlying milk sales going but in mid-June his cow needed veterinary attention costing almost 6,000 taka and stopped giving milk. Since then Samarth has had no cash income at all, and has paid for further treatment for the cow. Happily for him his various other interests have left him with cash reserves at home and deposits in the bank.

Rezia

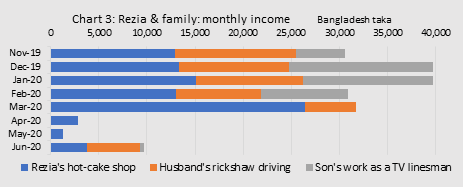

Our third featured diarist was Rezia whom we met in the third blog, where we described how, after a disastrous experience as an overseas worker, she had barely got her cake-shop up-and-running again when the lockdown forced her to close it. Chart 3 updates her story.

It shows that both her cake-shop and her husband’s rickshaw driving resumed in June. The income, however, was small. Rezia has been sick most of the month and although her son helped her open the shop for a few days they abandoned it after the middle of the month. She is now recovering her health and wants to re-open in early July. Her husband’s electric-assisted rickshaw battery had failed in late March and in the uncertain situation, he didn’t invest in a replacement until the end of June. The son managed only one day’s casual work as a linesman in June. His prospects remain poor.

It shows that both her cake-shop and her husband’s rickshaw driving resumed in June. The income, however, was small. Rezia has been sick most of the month and although her son helped her open the shop for a few days they abandoned it after the middle of the month. She is now recovering her health and wants to re-open in early July. Her husband’s electric-assisted rickshaw battery had failed in late March and in the uncertain situation, he didn’t invest in a replacement until the end of June. The son managed only one day’s casual work as a linesman in June. His prospects remain poor.

Was June better than May?

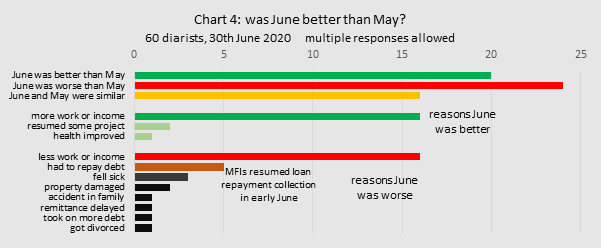

As these three updated stories suggest, June has been a mixed month. This is reflected in the survey we make at the end of each month, when we ask our diarists to tell us how the month compared to the previous month. Chart 4 summarises the results for the end-June survey.

The responses this time were much more nuanced than last month, when only two diarists out of 60 reported that May had been worse than April. Back then, they liked the fact that the lockdown, though still in place, had been eased, with far fewer police and troops on the street, and work, however limited, could be resumed. Many also enjoyed the Eid festival, which fell on May 25th. But this time, despite the fact that the lockdown was fully and officially lifted on May 31st, more found that in June things had got worse, mostly because work and income had deteriorated. Five microfinance borrowers regretted that they now had to resume their weekly repayments.

Newspaper vendor Liakat and cake-shop proprietor Rezia were among those who reported that things had improved, while farmer Samarth, as you might expect, said things had deteriorated. We can set these individual opinions against the overall picture for all sixty diarists by looking at some of the key trends that show up in the transaction records.

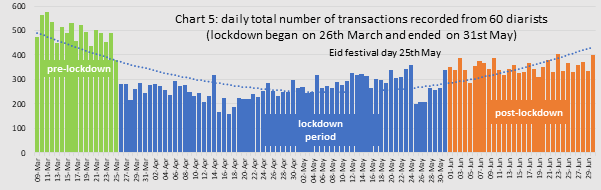

Chart 5 shows the number of transactions of all types (all inflows and outflows) that we recorded each day. The slump in this number was one of the clearest indicators we had that something dramatic had happened on March 26th, the day the lockdown started. As we see in the chart, the number has risen somewhat and has been fairly consistent each day during June, but our diarists are still not transacting as often as they did before the lockdown.

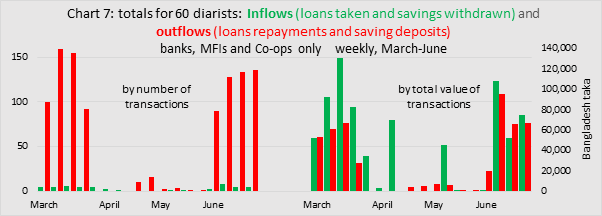

The main economic trends are shown in the next chart, Chart 6. We can clearly see just how badly earned income tumbled when the lockdown arrived, how its recovery since then has been erratic, and how it is still not back to pre-lockdown days. Household expenditure is seen to have been very low through most of April – around 12,000 taka per day shared out among 60 households, or about $2.45 a day per household at market exchange rates. It rose as the Eid festival approached (May 25th), then slumped again and still remains below pre-lockdown levels. The business costs, which have begun to rise again after a long dip, are mostly incurred by the shopkeepers and other retailers in our sample, who have to purchase stock.

What was the effect of the lockdown on our diarists’ the savings and borrowing?

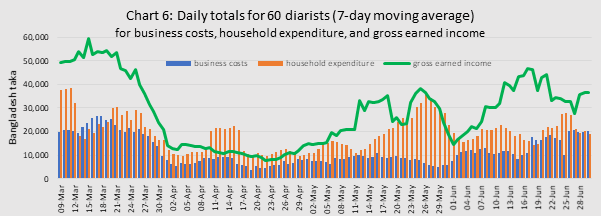

We explore this in Chart 7, which shows all borrowing and saving transactions made by our diarists with formal partners – mostly MFIs but also Banks, Insurance Companies and Co-ops. It does not show transactions made with informal partners such as informal borrowing with or without interest, or neighbourhood savings and loan clubs. The left side of the chart shows the number of transactions: we see the large number of small deposits and repayments that our diarists make compared with the much smaller number of loans taken or withdrawals made. The right hand side shows the combined values of these transactions.

The chart vividly shows the lull that set in when the lockdown started and persisted through May. This was mainly because MFIs were asked to close down during the lockdown, though one or two of them managed to do a little business, as did the Banks and a Co-op. The MFIs started disbursing and collecting again in early June. Interestingly, the value of inflows (loans taken and savings withdrawn) was higher than usual in the lead up to the lockdown (over any given period inflows and outflows tend to be of similar value). This may suggest that people stored money at home in expectation of difficult times ahead, and that in turn would help explain why households got through the harshest period with enough cash on hand to avoid the need to skip meals. After three decades of exposure to microfinance work, our diarists are sophisticated users of financial services. For example, they hold between them $57,286 of savings (at PPP exchange rates) at Banks, MFIs, Insurance Companies and Co-ops, exceeding the $45,050 of outstanding loans they hold.

June was an uncertain month

None of our diarist households caught the disease. None of them suffered severe deprivation. Many of them got back to work, and they started buying and selling and borrowing and saving again. But these activities are still being carried out at levels below what was normal before the lockdown. Hopes for the future remain constrained, as we see in the section of our monthly survey where we ask our diarists what plans, if any, they have for the following month. Three diarists said they were thinking of making some change in their occupation: a restaurant owner is thinking of moving to a new location, a welder believes he’ll have to go back to farm labour, and a cycle and rickshaw repair mechanic thinks business is so bad he’ll have to get a rickshaw of his own and drive it. A few others had family-related plans, a few hoped to resume home improvement work, and several said they had begun to plan for Eid ul Adha, the next festival in the Muslim calendar, due at the end of July.

But fully 34 of the 60 diarists said they have no plans for July. Diarists are aware that the incidence of Covid-19 is growing quickly in Bangladesh, if not yet in their locality, and the knowledge is oppressive. Like us, they are still waiting to see what will happen next.

Stuart Rutherford

July 4th 2020

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.

All fieldwork for the Hrishipara Daily Diaries Project is now being funded by L-IFT. We gratefully acknowledge their invaluable support.

Read more analysis based on the Hrishipara Diaries:

- Low-income households in Bangladesh give as well as take loans

- Education and Occupations

- How are Digital Financial Services used by poor people in Bangladesh?

- What the poor spend on health care?

- How the poor borrow?

- What do poor households spend their money on?

- Tracking the savings of poor households

- When poor households spend big

- When poor households spend big part 2

- Poverty measurement using data from the Hrishipara daily financial diaries

- Receiving Gifts in Low-Income Households

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.