GDI Lecture Series: Capitalism and Conservation in the Age of Security with Professor Libby Lunstrum

On Wednesday, 9th November Professor Libby Lunstrum from York University in Canada discussed Capitalism and Conservation in the Age of Security: The Vitalization of the State You can find the video and podcast from the event below.

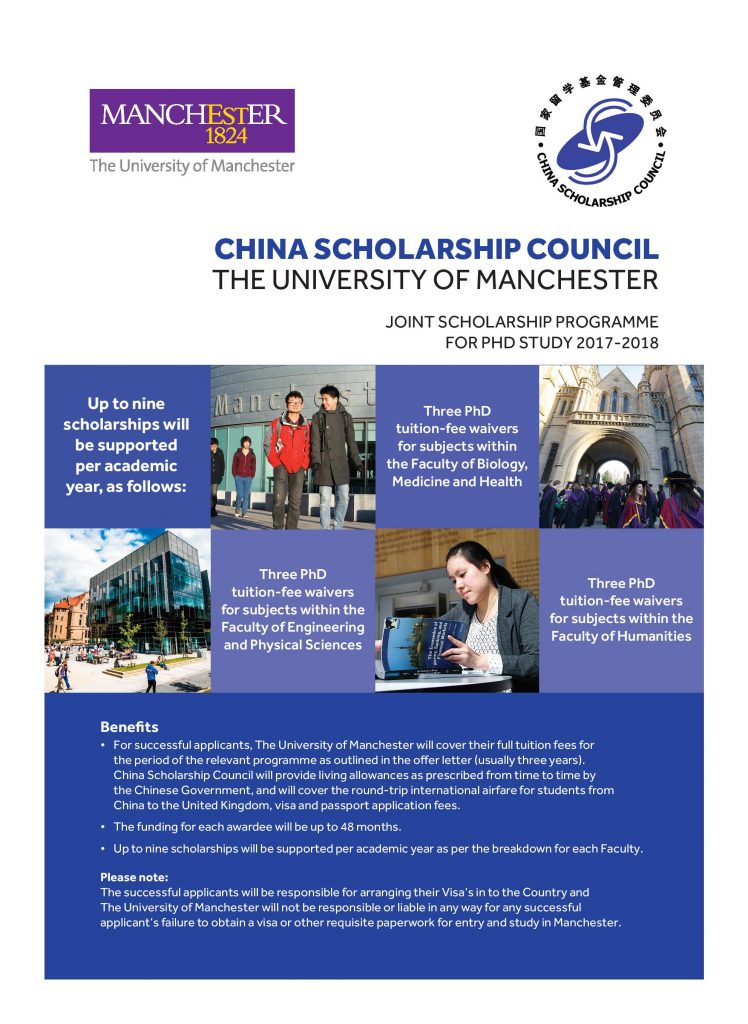

China Scholarship Council (CSC) – University of Manchester Joint PhD Scholarships 2017-18

Watch | Bina Agarwal at the New School for Social Research

On Tuesday, 25 October Bina Agarwal gave a lecture at the New School for Social Research in New York.

Her lecture demonstrated how women face deep inequalities in rules, norms, and social perceptions, which, in turn, create severe inequalities in their access to both private and public property. Based on her research, she challenged standard economic analysis to show how these inequalities undermine both economic efficiency and social justice. She also outlined pathways for change, such as enhancing women’s bargaining power in multiple arenas: the family, community, markets, and state. read more…

Brazil in political crisis: what has happened, and what might it mean for development?

IRIBA’s research has argued that in recent decades Brazil has followed a distinctive development trajectory. This has centred on inclusive growth and the use of innovative tax-financed social policy in reducing poverty and inequality and bolstering long term human development. However, current events are rather more bumpy, including a bona fide political crisis of dizzying proportions. What is going on and what might be the implications for development? I’ll take those in turn. Firstly, a not-entirely-impartial synopsis:

What is happening politically?

President Dilma Rousseff, of the centre-left Workers’ Party (PT) was impeached in a vote by Congress, and her administration supplanted by one headed by the centre-right Michel Temer (PMDB). Dilma was culpable forwindow-dressing government accounts to make public spending appear lower. This followed huge demonstrations mobilised under an ‘anti-corruption’ motif. So, a victory for people-power holding corrupt politicians to account, right? read more…

The Global Development Institute is Hiring

What do poor households spend their money on?

By Stuart Rutherford, Honorary Research Fellow at The Global Development Institute

The ongoing Hrishipara Daily Diary project records the daily money flows of 50 low-income households living near a market town in central Bangladesh. More details about the project, and about the relative poverty levels of the ‘diarists’ are given in another blog. 22 of the diarists – we call them the ‘extreme poor’ and the ‘very poor’ – have incomes below the ‘$2 a day per person PPP’ level. The 28 with higher incomes we categorise as ‘moderate poor’ and ‘near poor’.

The composition of total outflows

Our data collection records all the money that flows in and out of the diarists’ hands. We begin with a chart that shows the main categories of the total outflow. read more…

GDI Lecture Series: The UK’s Post-Brexit Trade Deal with Professor Alan Winters

On Wednesday, 26th October Professor Alan Winters discussed the UK’s Post-Brexit Trade Deal. Professor Winters is a Professor of Economics at the University of Sussex and former Chief Economist at the Department for International Development. You can find the slideshare, video and podcast from the event below. read more…

Rising Powers at the DSA 2016: China and the rising powers as development actors

By Corinna Braun-Munzinger, PhD researcher at the Global Development Institute

The Rising Powers Study Group of the Development Studies Association (DSA) and the ESRC Rising Powers and Interdependent Futures programme jointly convened a full-day panel at the DSA annual conference in Oxford on 13 September, titled “China and the rising powers as development actors: looking across, looking back, looking forward”. These issues were approached from various angles – ranging from a macro perspective on fundamental shifts in the global world order to the micro-level perceptions of individual development workers in South-South cooperation.

The Rising Powers Study Group of the Development Studies Association (DSA) and the ESRC Rising Powers and Interdependent Futures programme jointly convened a full-day panel at the DSA annual conference in Oxford on 13 September, titled “China and the rising powers as development actors: looking across, looking back, looking forward”. These issues were approached from various angles – ranging from a macro perspective on fundamental shifts in the global world order to the micro-level perceptions of individual development workers in South-South cooperation.

The discussions began from a broad perspective on how the rising powers influence development prospects globally. Rory Horner, University of Manchester, started out by tracing how the traditional distinction between developed and developing countries has become blurred as a result of the emergence of the rising powers, calling for more research on a beginning new era of more universal, global development. Albert Sanghoon Park, University of Cambridge, complemented this forward-looking perspective by taking a look back at the historical geopolitical patterns underlying the developed-developing country dichotomy since the 1940s. Seen from this angle, possible tensions between the ideals and the geopolitics of development are neither new, nor are they likely to disappear with the rising powers taking on stronger roles in shaping global development. Following from these broader thoughts, Anna Wrobel, University of Warsaw focused on trade policy as one specific aspect in which China engages in shaping the global economic order, both through the WTO and through bilateral agreements.

Pharmaceuticals and the Global South: a healthy challenge for development theory?

Dr Rory Horner, Lecturer, Global Development Institute

Dr Rory Horner, Lecturer, Global Development Institute

With the potential to ameliorate pain and even save lives, pharmaceutical products can have greater impact than those of almost any other. Yet, in overviews of research on development, somehow the pharmaceutical industry does not feature as prominently as, for example, extractive industries or textiles.

In a new article in Geography Compass, I argue that the pharmaceutical industry can tell key stories for development – in particularly highlighting the need to bridge the oft-present dichotomy between the economic and industrial or social aspects of development.

For a long time, it appeared that there was little positive to say about the pharmaceutical industry in relation to its contribution to development. Post-independence, most developing countries found themselves relatively dependent on multinational companies for the imported supply of medicines and the sector was widely viewed as exemplifying the problems of dependent development. In the 1970s, the establishment and promotion of local pharmaceutical production attracted considerable policy interest among developing countries seeking to overcome the dependence on multinationals from the global North, with some support from United Nations Conference on Trade and Development and United Nations Industrial Development Organization. Yet, many countries, like Pakistan and Sri Lanka, faced a backlash from multinationals and few succeeded. Even in those limited cases where efforts to promote local industry did succeed, such as India and Argentina, the immediate benefits for health were questionable. Particularly from a public health perspective, the struggles with the pharmaceutical industry ranged from questions of production to such issues as essential drugs, marketing, quality control, price control, pooled procurement and the utilisation by health workers and patients. read more…

What does Habitat 3’s New Urban Agenda mean for the displaced?

By Luis Eduardo Perez Murcia is a PhD researcher at The Global Development Institute

By Luis Eduardo Perez Murcia is a PhD researcher at The Global Development Institute

This month more than 25,000 delegates meet in Quito, Ecuador, for the Habitat 3 conference which sets out the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda – a guide to policies and approaches for the sustainable development and planning of cities and towns across the globe for the next 20 years. As part of The University of Manchester’s research beacon for Addressing Global Inequalities, we bring you a special series of blogs from some of our leading researchers.

In our fourth and final post of this series, Luis Eduardo Pérez Murcia relates the UN’s New Urban Agenda to one asylum seeker’s experience.

The lottery of life

20, 28, 42, 57, 107, 111 and 114b. These are not winning numbers. They are the numbers of the seven clauses which reference “the displaced” within the New Urban Agenda – and yet perhaps in that regard they could create winners in the lottery of life, if the agenda achieves its aspirations over the next 20 years.

Perhaps clause 28 is the strongest aspiration of how Habitat 3 hopes to aid the home lives of the displaced: “We further commit to strengthen synergies between international migration and development, at the global, regional, national, sub-national, and local levels by ensuring safe, orderly, and regular migration through planned and well-managed migration policies and to support local authorities in establishing frameworks that enable the positive contribution of migrants to cities and strengthened urban-rural linkages.”

So let’s move for a moment from the broad aims above to my research experience of one person’s reality. An area of research interest for me has been the ongoing war in Syria which has left millions of people displaced either within or across national borders.

A story of one Syrian…

Noor came to England as an international student in 2014. She is an example of how not all Syrian asylum seekers and refugees fled following direct threats and violence. As Noor’s experience illustrates, some left their country to pursue professional and academic careers but, because of war, cannot return.

Noor was accepted by The University of Manchester but was concerned about whether or not she would be able to obtain a visa, having heard that visas for Syrians – even those who are sponsored students – were being rejected. However, Noor was able to study here and upon finishing her studies she returned ‘home’ as planned.

However, after only one day at home in Damascus it became clear that what the international media called an ‘uprising’ and later a ‘crisis’ was indeed a ‘war’. ‘Home’ was no longer a safe place in which Noor could pursue her dreams and achieve her aspirations. When she returned to Manchester to attend her graduation ceremony it crossed her mind that England, a place in which she had had such a wonderful and productive time, could become her next home. She applied for refugee status and immediately shifted from being an international student to being an asylum seeker.

“Home is the place you feel you can contribute the most”

“Home is the place you feel you can contribute the most”

Noor’s story tells us something about what and where home is and what it means. She says that “home” is a tricky concept and one that is hard to define. Ultimately she says, “Home is neither my country nor the physical house where I was living in Damascus. Home to me is more a feeling”. Having spent a significant part of her life living in other countries including France, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon and England, Noor says, “I see life as a train station. I am always ready to move”.

Noor experiences home as a mobile space. “I feel at home in a place I like. I think family is central for my understanding of home but home is also the place you feel you can contribute the most. I am volunteering as a research assistant and bringing support to refugees in the UK, so I think England could now be my home”.

This personal feeling of Noor is very much in line with Clause 28 of the New Urban Agenda which aspires to “enable the positive contribution of migrants to cities and strengthened urban-rural linkages.”

She stresses that she is an independent woman able to work and contribute to society just like other refugees. She added, “If I am granted permission to stay, I will work, I will pay taxes and I will do my best to contribute to this society”.

Papers and envelopes

However, waiting for the Home Office concerning her status in the UK is not free of tension and she is anxious about the future. Noor told me “I feel trapped in limbo. I am not saying I feel in limbo living in England. I can make this place my home. What I mean is that I feel trapped in limbo with my Syrian passport. I cannot work or move anywhere. In order to feel at home I need papers. I need the permission to stay”.

Noor’s emphasis on the need of ‘papers’ to feel at home in England can be better understood if we consider the role of the symbolic value of material things in the process of home-making. I asked Noor if she had brought anything with her to England that reminded her of home in Damascus. The answer was an envelope which Noor brought to England. It contains her academic diplomas, language test results, letters of reference and her passport. When asked why she chose the envelope she simply replied, “That is what I am. Thus, that is what I need to make a home for myself in this country”.

What will the New Urban Agenda can mean for people like Noor?

Noor’s experience is only one of millions of Syrians who have fled conflict or who cannot return to their country because of the escalation of war. Having to make a new home away is an experience shared by many of the over 60 million people currently living in conditions of displacement across the world.

Her experience helps us to unveil the multiple challenges of putting in practice complex clauses of the New Urban Agenda. How governments, policy makers and the international community can strengthen synergies between international migration and development (clause 28) when asylum seekers are not entitled to the right to work in many countries is just one issue raised by Noor. A significant challenge is therefore how to ensure that displaced persons, both those who move within and across national borders, are able not only to make a living but also to find their place in the cities where they are already settled or aspire to migrate.

Thus, rather than thinking of migration as a problem and migrants as people who need to be kept in their place, the big challenge for the new urban agenda is to understand migration as an historically constructed practice and migrants as purposive actors in the city landscape. Displaced persons, as sociologist and researcher Dr Maja Korac stresses, are ordinary human beings living in extraordinary circumstances.

They are just people like us trying to find a safe place to live in the world.