What does Habitat 3 mean for people affected by climate change?

By Joanne Jordan, Lecturer in Climate Change & Development at the Global Development Institute

This month more than 25, 000 delegates meet in Quito, Ecuador, for the Habitat 3 conference which sets out the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda – a guide to policies and approaches for the sustainable development and planning of cities and towns across the globe for the next 20 years.

As part of The University of Manchester’s research beacon for Addressing Global Inequalities, we bring you a special series of blogs from some of our leading researchers. Here, Joanne Jordan talks about the importance of capturing local voices and ideas, if the UN’s New Urban Agenda and Habitat 3 visions for sustainable cities is to be realised.

Bold statements

Under Point 13G of the New Urban Agenda sits a very bold statement: “We envisage cities that adopt and implement disaster risk reduction and management, reduce vulnerability, build resilience and responsiveness to natural and man-made hazards, and foster mitigation and adaptation to climate change.”

This is an important aspiration and one close to my heart, experiences and research in Dhaka – the capital of Bangladesh and a place on the front line of climate change. As part of my research on climate change at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute, I spent months in a slum in Dhaka talking to over 600 people in their homes, work places, local teashops and on street corners to understand how climate change affects their ‘everyday’ lives and what solutions they employ.

This is an important aspiration and one close to my heart, experiences and research in Dhaka – the capital of Bangladesh and a place on the front line of climate change. As part of my research on climate change at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute, I spent months in a slum in Dhaka talking to over 600 people in their homes, work places, local teashops and on street corners to understand how climate change affects their ‘everyday’ lives and what solutions they employ.

So what might the New Urban Agenda mean to the people living in Dhaka’s slums? Currently, most mainstream work on reducing inequality doesn’t take into account the different risks that people face as a result of climate change and this means that the interventions aimed at reducing inequality are likely to be less effective.

Most people who are adversely affected by climate change are already poor and are likely to become poorer as a result of it. Inequality affects how people respond to climate change. My research looks at how those responses differ and why. This can point to what kinds of interventions will help even out the playing field.

Innovation and land right issues

My research found that the urban poor have been able to develop a myriad of innovative ways to respond to climate change but in many cases their efforts are constrained by a lack of land tenure rights. For example, if slum dwellers are not protected by laws and regulations that shield them from exploitative landlords, they are less likely to invest scarce resources in making their homes more resilient to climate change.

Limited resources can also trap the poor in places that flood most frequently because they cannot afford rents elsewhere. One slum dweller explained: ‘The water came up to my waist, our houses drown. Where can we go? The more water, the less the rent. The rent is low here. The owner is going to raise the land, but the rent will go up. This will not help me. We will move somewhere else. We are poor, wherever we can get cheap rent, we move there.’

Broadcasting local voices

Throughout my time as a researcher, I have been a firm advocate of innovative approaches that capture and share the voices of local people.

So once my research in Dhaka was complete, I teamed up with the Department of Theatre and Performance Studies at the University of Dhaka to explore the findings through a ‘Pot Gan’ – a traditional folk medium that combines melody, drama, pictures and dancing.

The Pot Gan we developed was an interactive event that challenged the audience to engage with the personal experiences of slum dwellers affected by climate change.

Live performances of ‘The Lived Experience of Climate Change: A Story of One Piece of Land in Dhaka’ have now been seen live by over 600 people, including Dhaka slum dwellers, policy makers, practitioners, academics and the general public. At the time of publishing this blog, a documentary on the Pot Gan has been viewed by over 50,000 people.

The New Urban Agenda: time to engage?

The New Urban Agenda: time to engage?

If you look at any given intervention, its success depends on whether it fits with people’s everyday experiences and understanding of climate change. Therefore, to create effective climate resilience strategies, it is crucial that we engage local voices in innovative ways to ensure that we do not leave the disadvantaged and most vulnerable behind by predefining their ‘problems’ and bypassing their priorities and realities. My project provided a platform for the ‘voices of the urban poor’ to enter the climate change debate – challenging us to inclusive action and critical thought.

And this mirrors my hopes and advice to those driving forward Habitat 3’s New Urban Agenda. I say: do not forget to engage the very people you strive to help. As you roll out the agenda over the next 20 years, consider approaches that may be new or different for you – as Pot Gan was for me – but which give a voice and a greater understanding of the changes you seek to bring about by putting the power in the hands of the very people who are finding ways every day to “reduce vulnerability, build resilience and responsiveness.”

Whilst the New Urban Agenda must operate at a national and strategic level to bring about a greater good, let it not forget about engaging and projecting the voices and ideas of the local people it aims to serve.

A documentary and video of the Pot Gan performance is available at https://bit.ly/GDIpotgan

How can Habitat 3 and the New Urban Agenda turn inequality talk into action?

By Diana Mitlin, Managing Director of the Global Development Institute and academic lead for the University’s Addressing Global Inequalities research beacon.

By Diana Mitlin, Managing Director of the Global Development Institute and academic lead for the University’s Addressing Global Inequalities research beacon.

This month more than 25,000 delegates meet in Quito, Ecuador, for the Habitat 3 conference which sets out the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda – a guide to policies and approaches for the sustainable development and planning of cities and towns across the globe for the next 20 years. As part of The University of Manchester’s research beacon for Addressing Global Inequalities, we bring you a special series of blogs from some of our leading researchers.

Ahead of next week’s conference when delegates will set out the United Nations’ New Urban Agenda, Diana Mitlin suggests three principles to aid their success.

The New Urban Agenda promises everything. It’s based on the three core principles of leaving no-one behind, sustainable and inclusive urban economics and environmental sustainability.

But the agenda begins with recognition of the problem of growing inequalities, alongside other obstacles to achieving sustainable development. Against these barriers, can it deliver? Will the Agenda succeed in reducing the inequalities that so many people I have worked with face on a day to day basis?

Ask anyone living in informal settlements, and they will tell you that their residency is a cause of discrimination. That’s due to the negative assumptions that higher-income people make about people who live in areas characterised by a lack of secure tenure, safe living conditions and adequate access to basic services.

This is not a problem that will just disappear. The number of people living in informal settlements is predicted to rise from just over 860m “slum dwellers” today to over 900m by 2030. How can both this rising trend, and the needs of those estimated 900m people, be addressed?

A model example?

One example of a programme that needs to be expanded if the New Urban Agenda is to be realised is Transforming Settlements for the Urban Poor. A Ugandan government programme, which is financed by the World Bank and realised in partnership with the National Slum Dwellers Federation of Uganda in 14 towns and cities across Uganda, it involves over 14,000 informal settlement residents working alongside their local governments. The programme provides funding to construct essential services such as water points and public toilets.

Its progress is far from perfect – yet it is a model of the sort of alternative approach that enables transformative change by supporting the understanding of local struggles and implementing relevant action on the ground.

Its progress is far from perfect – yet it is a model of the sort of alternative approach that enables transformative change by supporting the understanding of local struggles and implementing relevant action on the ground.

So why does it work? Here are three things could the New Urban Agenda learn from it.

- Platforms for dialogue and monitoring

One of the most effective tools for improved governance has been the Municipal Development Forums that bring together community leaders from informal settlements, government officials and other active stakeholders in towns and cities. Forum meetings every one to three months enable perspectives to be understood, problems shared and priorities to be set. - Engagement in implementation

It is critical for community members to own the improved infrastructure. Experience has shown that community contracting ensures that local communities are involved, and that at least some of the income generated by infrastructure investments is circulated within the informal settlements, benefiting informal businesses. - Agreed reporting around metrics

What emerges from the Federation’s research work and that of an NGO in Uganda called ACTogether which facilitates capacity building at a local level and pro-poor policy promotion, is the importance of agreed metrics to report on progress made. Monitoring the numbers, using facilities such as toilet blocks, is important. But the costs of access are also critical. Equally important is understanding the value added to land because of these public investments, and making sure that the most disadvantaged citizens are not excluded as services are improved and rents increase.

Yes, the New Urban Agenda promises much – but it is short on how delivery will happen. We need to re-orientate our discussions. What has been learned from experience to date about how progressive change happens? What do the National Slum Dwellers Federation of Uganda see as important to reduce the growth of informal settlements? How can existing efforts being made by local residents and their local authorities be scaled up and multiplied?

Only then, and using the three principles outlined here, can we improve access to services and secure tenure. This is when we will finally put in place support measures that reduce the numbers living in informal settlements, making lives less precarious – and enabling 900m more people to receive more of the benefits offered by development.

Diana will be live tweeting from Habitat 3 at @GlobalDevInst between 17 and 20 October.

This blog post is also published by CityMetric and Policy@Manchester

Read our other Habitat 3 coverage

Data Justice for Development

By Richard Heeks, Professor of Development Informatics

What would “data justice for development” mean? This is a topic of increasing interest. It sits at the intersection of greater use of justice in development theory, and greater use of data in development practice. Until recently, very little had been written about it but this has been addressed via a recent Centre for Development Informatics working paper: “Data Justice For Development: What Would It Mean?” and linked presentation / podcast.

Why concern ourselves with data justice in development? Primarily because there are data injustices that require a response: governments hacking data on political opponents; mobile phone records being released without consent; communities unable to access data on how development funds are being spent.

But to understand what data justice means, we have to return to foundational ideas on ethics, rights and justice. These identify three different mainstream perspectives on data justice:

- Instrumental data justice, meaning fair use of data. This argues there is no notion of justice inherent to data ownership or handling. Instead what matters is the purposes for which data is used.

- Procedural data justice, meaning fair handling of data. This argues that citizens must give consent to the way in which data about them is processed.

- Distributive data justice, meaning fair distribution of data. This could directly relate to the issue of who has what data, or could be interpreted in terms of rights-based data justice, relating to rights of data privacy, access, control, and inclusion / representation.

We can use these perspectives to understand the way data is used in development. But we also need to take account of two key criticisms of these mainstream views. First, that they pay too little attention to agency and practice including individual differences and choices and the role of individuals as data users rather than just data producers. Second, that they pay too little attention to social structure, when it is social structure that at least partly determines issues such as the maldistribution of data in the global South, and the fact that data systems in developing countries benefit some and not others.

We can use these perspectives to understand the way data is used in development. But we also need to take account of two key criticisms of these mainstream views. First, that they pay too little attention to agency and practice including individual differences and choices and the role of individuals as data users rather than just data producers. Second, that they pay too little attention to social structure, when it is social structure that at least partly determines issues such as the maldistribution of data in the global South, and the fact that data systems in developing countries benefit some and not others.

To properly understand what data justice for development means, then, we need a theory of data justice that goes beyond the mainstream views to more clearly include both structure and agency.

The working paper proposes three possible approaches, each of which provides a pathway for future research on data-intensive development; albeit the current ideas are stronger on the “data justice” than the “for development” component:

- Cosmopolitan ideas such as Iris Marion Young’s social connection model of justice could link data justice to the social position of individuals within networks of relations.

- Critical data studies is a formative field that could readily be developed through structural models of the political economy of data (e.g. “data assemblages”) combined with a critical modernist sensitivity that incorporates a network view of power-in-practice.

- Capability theory that might be able to encompass all views on data justice within a single overarching framework.

Alongside this conceptual agenda could be an action agenda; perhaps a Data-Justice-for-Development Manifesto that would:

- Demand just and legal uses of development data.

- Demand data consent of citizens that is truly informed.

- Build upstream and downstream data-related capabilities among those who lack them in developing countries.

- Promote rights of data access, data privacy, data ownership and data representation.

- Support “small data” uses by individuals and communities in developing countries.

- Advocate sustainable use of data and data systems.

- Create a social movement for the “data subalterns” of the global South.

- Stimulate an alternative discourse around data-intensive development that places issues of justice at its heart.

- Develop new organisational forms such as data-intensive development cooperatives.

- Lobby for new data justice-based laws and policies in developing countries (including action on data monopolies).

- Open up, challenge and provide alternatives to the data-related technical structures (code, algorithms, standards, etc) that increasingly control international development.

This blog originally appeared on the ICTs for Development website.

How does India engage with sustainability standards?

By Natalie Langford, PhD research at the Global Development Institute

By Natalie Langford, PhD research at the Global Development Institute

In November, the Rising Powers and Global Labour Standards team will be travelling to India in order to jointly host a conference alongside Centre for Responsible Business (CRB), a prominent NGO based in New Delhi. ‘India and Sustainability Standards: International Dialogues & Conference’ (ISS 2016) takes place from the 16-19th November. It presents an exciting opportunity for us to disseminate our research and engage to a broad audience of stakeholders involved in the sustainability field in Asia.

The broader theme of the ISS conference is the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and how the corporate sector can contribute towards achieving these ambitious goals. There is a broad consensus that governments alone will not be able to meet these goals. However, our research demonstrates there are key roles that government departments and agencies need to play to ensure that businesses can operate efficiently while contributing towards sustainable development.

Our project, led by Professor Khalid Nadvi at the Global Development Institute has been concerned with how global labour standards affect production processes, and the ways in which various actors have engaged with the shaping of such standards. Our research has important implications for how effective labour standards can foster responsible business practices.

Whilst privately governed ethical standards (such as Rainforest Alliance or Forestry Stewardship Council) have become a key feature of global value chains in which goods and services are sold in Northern markets, there is a growing interest in the ways in which standards may emerge in global value chains across the Global South. Given the huge growth in production and consumption in , Southern markets, it is especially important to understand the extent to which actors in the Global South are also shaping labour standards for local markets.

Whilst privately governed ethical standards (such as Rainforest Alliance or Forestry Stewardship Council) have become a key feature of global value chains in which goods and services are sold in Northern markets, there is a growing interest in the ways in which standards may emerge in global value chains across the Global South. Given the huge growth in production and consumption in , Southern markets, it is especially important to understand the extent to which actors in the Global South are also shaping labour standards for local markets.

India is one of the three Rising Powers (alongside Brazil and China) in which the project has conducted extensive qualitative and quantitative research, in order to examine this phenomenon. Given that states, firms and civil society organisations are all recognised actors engaged in standard setting, the core research questions of the project focused upon the ways in which these different sets of actors had been exposed to global labour standards, their perspectives and experiences, and the ways in which they seek to shape (or not) labour standards for markets in the Global South.

As a PhD student on this project, I have been lucky enough to gain a great deal of insight into the ways in which Brazil, China and India have engaged with the standards agenda through my interactions with the senior academics attached to the project. Professor Nadvi has assembled a truly global team of academic experts; from local colleagues at Alliance Manchester Business School through to Professors based in India, China and Brazil who have all contributed their knowledge and experience to the project.

My own research has focused on India in particular, and the conference is an opportunity for me to present my findings on Trustea, a new standard for the Indian tea industry which is specifically focused on the domestic market. I explore the role of both global and national actors within the development of the standard, and how the interactions between state, civil society and lead firms within Trustea has contributed to new forms of governance of social conditions within the Indian tea industry.

My own research has focused on India in particular, and the conference is an opportunity for me to present my findings on Trustea, a new standard for the Indian tea industry which is specifically focused on the domestic market. I explore the role of both global and national actors within the development of the standard, and how the interactions between state, civil society and lead firms within Trustea has contributed to new forms of governance of social conditions within the Indian tea industry.

We’ll also be presenting our research related to Indian lead firms, civil society organisations and the state in relation to global sustainability standards. Professor Rudolf Sinkovics from Alliance Manchester Business School as well as Professor Peter Knorringa from the Institute for Social Studies (ISS), based in The Hague, Netherlands will all be discussing their latest findings as contributors to the Rising Powers project. The conference has been organised by Dr Bimal Arora, Chairperson for Centre for Responsible Business.

The conference will take place from 16-19th November at the India Habitat Centre (IHC), New Delhi. Register for a place. We will be tweeting live from the conference using @powers_rising

GDI Lecture series: Should Rich Nations Help the Poor? with Professor David Hulme

On Wednesday, 12th October 2016, Executive Director of the Global Development Institute, Professor David Hulme discussed his latest book, Should Rich Nations Help The Poor?. You can find the slideshare, video and podcast from the event below.

‘Sustainability Challenge’ offers valuable lessons for universities’ engagement with the public

By Judith Krauss, post-doctoral associate at the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College

In the biggest-ever event on campus, The University of Manchester ran the ‘Sustainability Challenge’ for its 8,200 first-year undergraduates, encouraging students to realise their tremendous role in the University’s social responsibility agenda. I helped facilitate the challenge and think that there are broader lessons for universities’ public engagement to be learned from this experience.

The Sustainability Challenge’s premise is that the University of Manchester’s undergraduates morph into members of staff at the fictitious ‘University of Millchester’. Diverse teams, deliberately mixing civil engineers and sociologists, medics and mathematicians, are tasked with developing a ‘Campus East’ which meets fiduciary obligations, but also complies with a hard carbon cap. Each option, for teaching and learning or accommodation, energy or transport, comes with social, economic and environmental advantages and disadvantages, the magnitude and constellations of which are based on research conducted at The University of Manchester. For instance, choosing the high-cost energy option will improve the campus’s carbon footprint, but also eat into the budget significantly. By contrast, choosing high-cost teaching and learning leaves little money for accommodation. Yet maybe the corporate sponsorship offers from a fast food chain or an oil company could offer budgetary respite?

The Sustainability Challenge’s premise is that the University of Manchester’s undergraduates morph into members of staff at the fictitious ‘University of Millchester’. Diverse teams, deliberately mixing civil engineers and sociologists, medics and mathematicians, are tasked with developing a ‘Campus East’ which meets fiduciary obligations, but also complies with a hard carbon cap. Each option, for teaching and learning or accommodation, energy or transport, comes with social, economic and environmental advantages and disadvantages, the magnitude and constellations of which are based on research conducted at The University of Manchester. For instance, choosing the high-cost energy option will improve the campus’s carbon footprint, but also eat into the budget significantly. By contrast, choosing high-cost teaching and learning leaves little money for accommodation. Yet maybe the corporate sponsorship offers from a fast food chain or an oil company could offer budgetary respite?

It was a privilege and a joy to be part of the Sustainability Challenge, with far more staff than just the 160 facilitators contributing to the research, preparation and implementation of the Challenge. The six student teams I got to meet were as enthusiastic in choosing their group names – Prestigious Innovative Food Ninjas Ltd., Green Queens and The Sustainables come to mind – as they were in devising and defending their diverse visions for Campus East: one team saw no issue with enlisting the corporate support of the oil company, as long as they spent the extra money on high-quality teaching and learning and offsetting carbon emissions. Others considered all sponsorship a sell-out. One team devised an eco-science park only generating minimal carbon emissions. All sought to create benefits for Campus East’s surrounding community.

The activity not only impressed students in terms of the University sparing no resources to put #GetSust into practice. They got to realise that sustainability has many facets and interpretations, which require diverse skills and have to be negotiated with various interest groups. And they experienced that every individual has a part to play in social responsibility and sustainability – an insight which I hope they will take into their studies and into their future positions of responsibility in public sector, business and civil society, where each of their choices will have impacts on social, economic and environmental sustainability.

The activity not only impressed students in terms of the University sparing no resources to put #GetSust into practice. They got to realise that sustainability has many facets and interpretations, which require diverse skills and have to be negotiated with various interest groups. And they experienced that every individual has a part to play in social responsibility and sustainability – an insight which I hope they will take into their studies and into their future positions of responsibility in public sector, business and civil society, where each of their choices will have impacts on social, economic and environmental sustainability.

Emphasising the complex nature of sustainability, but also the imperative it constitutes for everybody is where the Challenge in my view offers broader lessons for the way universities engage with stakeholders and the public.

Given a widespread discontent with ‘experts’ in public discourse, there is much work to be done by universities to allay suspicions of Ivory Towers unrelated, and unsympathetic, to what goes on around them. Equally, there is a need to make clear how the work of universities, through research and teaching, entails benefits for all of society despite high tuition fees and often inaccessible research outputs.

What the Sustainability Challenge teaches, in my view, is firstly that it is imperative, and fun, to make research accessible, through a game, a challenge, or an engaging activity which makes palpable the outputs of research funding, and will stay with the participants for a long time to come. Secondly, building on the contact hypothesis, institutes of learning have a chance, nay an obligation, to bring together people who may never have met otherwise, offering them a space to discover and engage with each others’ diverse foci, viewpoints and motivations. Finally, setting a clear task which can only be solved through collaboration sets free surprising abilities to cooperate, innovate and trust in the jointly produced solutions which no one could have devised alone.

I think we can go even further in terms of the Sustainability Challenge’s learning potential: I hope that future Sustainability Challenges, at Manchester and elsewhere, will not only issue an invitation to on-campus students, but use a question, format and implementation which is accessible and relevant far beyond one university or city. Evidently, there is no doubt that finding a question of interest locally and globally, a viable format, and the resources for preparation and implementation would no doubt be a mammoth Sustainability Challenge requiring collaboration beyond any one actor.

I think we can go even further in terms of the Sustainability Challenge’s learning potential: I hope that future Sustainability Challenges, at Manchester and elsewhere, will not only issue an invitation to on-campus students, but use a question, format and implementation which is accessible and relevant far beyond one university or city. Evidently, there is no doubt that finding a question of interest locally and globally, a viable format, and the resources for preparation and implementation would no doubt be a mammoth Sustainability Challenge requiring collaboration beyond any one actor.

However, an even greater Sustainability Challenge would be introducing societal benefits and sustainability awareness even more systematically into universities’ fabric than Manchester has already done. Examples could be placing social, economic and environmental sustainability at the heart of all curricula, making stakeholder and public engagement a compulsory element of undergraduate, postgraduate and PhD programmes, or requiring research outputs to be accompanied by jargon-free ‘accessible’ summaries.

Yet in my view, given the grand challenges of our time, the key role universities play in addressing them and the fundamental need to rethink universities’ responsibility towards society, the question is whether we can afford not to tackle this greatest ‘Sustainability Challenge’.

Staff Spotlight: Dr Rory Horner

Dr Rory Horner is an economic geographer and Lecturer, ESRC Future Research Leader and Hallsworth Research Fellow at GDI. He is originally from Ireland and holds a PhD in Geography from Clark University in the United States.

Dr Rory Horner is an economic geographer and Lecturer, ESRC Future Research Leader and Hallsworth Research Fellow at GDI. He is originally from Ireland and holds a PhD in Geography from Clark University in the United States.

What is the current focus of your research?

My research looks at globalisation, trade and the industrial development of the pharmaceutical industry, particularly the production and trade of generic medicines in the global South. I look at how and why production patterns emerge, and which ones under which conditions could improve social and health outcomes.

Currently, my specific focus – supported by an ESRC Future Research Leader Award (2016-2019) – is on Indian pharmaceutical companies and their engagement with Sub-Saharan Africa. I am initially trying to shine a light on the dynamics of how the value chain operates, while considering some broader issues related to industrial development and health. Indian medicines are known to many as the “pharmacy to the developing world” because of the large volume of supply at a relatively lower cost than elsewhere. For some, these imports create a health dependence issue for developing countries, which is being combatted by a push for local production across much of Sub-Saharan Africa. A big current debate questions whether developing countries should domestically produce as much of their own medicines as possible or should the pharmaceuticals supply largely come from only large developing countries (such as India or China) or even Europe or North America? And which supply may be better for public health?

What is the biggest hurdle in the system?

The first is that the whole system is quite opaque and there is relatively little evidence available on the dynamics of the pharmaceutical industry in this context. Policymakers need this evidence to make decisions that are actually based on a concrete understanding of the dynamics – right now, the picture is far too fragmented.

Policy coordination is another big issue. On a national level, different aspects of the pharmaceutical industry fall under the different ministries, creating competing priorities or at least some disagreement. In South Africa, for example, there is debate between the relevant departments for industry and health: the first would like to promote South African manufacturers but the latter generally finds that it is more cost effective to buy the medicines it needs from India. The counter argument from the Department of Trade and Industry is that the longer term health outcomes are better if South African manufacturers are promoted to claim more domestic control over medicine supply. Of course, the dynamics between the different stakeholders are different depending on the country in question, but most are complex.

Why is this ESRC Future Research Leader research project important?

India is currently sending a large volume of medicines to developing countries, and there are claims made that this benefiting all parties concerned. But is that really the case? From the India angle, we need to trace out how “India’s pharmacy to the developing world” actually plays out. Does it really function the way it is perceived and is it really a win-win situation where India and people elsewhere in the Global South (from consumers to patients) all benefit?

The other angle is to look at the dynamics in the African countries, where the issues centre around local production, the effects of the dependence on imported, and the potential situation of health insecurity on one side, but also the potential health benefit of large volumes of relatively lower-cost medicines on the other side. For countries that have had smaller regulatory capacities to govern what drugs are imported, locally produced or how they are marketed and sold, who is keeping an eye on quality? All of these issues have potential significance for social and health outcomes for millions of people.

Finally, pharmaceuticals are an under-researched industry for development. I recently wrote a paper on why pharmaceuticals are important for development theory – basic development courses will frequently talk about the natural resource curse or labour standards in textile industry, but rarely delve into the pharmaceutical industry, which has a lot of broad lessons for students and researchers on the balancing act between promoting industrial development while delivering optimal social and health outcomes.

How does your work address global inequalities, one of The University of Manchester’s research beacons?

In two distinct ways. Firstly, access to medicines is a huge global inequality. Most developing countries don’t have health insurance systems, and certainly not of the kind that you find in the UK. This means that most people rely on their own private expenditure to pay for their medicines. So, the price of those medicines directly affects millions – and not just whether the medicine is cheap, but is it of the same quality and will it treat just as effectively as the pricier versions? My research tries to look at the underlying industrial mechanisms that eventually determine price and access to medicines, understanding the economic and wider social, political and health dimensions of development through that.

Secondly, between different countries, there’s huge variation in the price of medicines and in the underlying capacity to produce medicine. Different countries find themselves in very different bargaining positions when dealing with global donors or setting trade policies related to pharmaceuticals, for example. A country that is dependent on multinationals from Europe and North America for their medicines may find it difficult to implement policies in favour of generic medicines. There is also a clear North/South divide on critical patent protection issues that could create significant obstacles for the supply of generic medicines.

What is your favourite thing about GDI? Or what do you enjoy the most?

What is your favourite thing about GDI? Or what do you enjoy the most?

The international environment and context: both the student body and the colleagues I work with, who come from many different countries and backgrounds. We are also international in terms of outlook and orientation – there is broad support and interest for globally oriented teaching and research that involves fieldwork all over the world.

Also, the connectivity: there are so many opportunities to engage with different types of networks and colleagues, from workshops to high-profile guest lecturers. You feel well connected to the development studies and policy worlds, and in a good place to make new and relevant connections when working here.

What advice would you give to a PhD student?

It’s important to make sure that you’re producing tangible outputs (from papers to public engagement), but it isn’t all about the thesis: a PhD is a professional training that should provide you the basic skill set that you can build up as you grow as a researcher and teacher.

Who is your development hero?

Going by my EndNote files, probably Peter Evans and Gary Gereffi. The first has done a huge amount of work on the global economy, the latter on global value chains – but both started out doing research on pharmaceuticals! The shared interest in pharmaceuticals is coincidental though, I really enjoy and find relevance in all of their work. If I was pressed to choose one, it might be Evans, who wrote a pivotal book about the developmental state and really challenged the idea that the state didn’t matter for development.

What do you do when you’re not busy with research?

I used to row competitively but fieldwork cut into my training schedule. I still row, cycle, and am generally outside doing some kind of sport. Running is a favourite no-equipment option in the field!

Lose neither your hair nor your head: Six tips for starting the PhD journey

By Judith Krauss, post-doctoral associate at the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College

How do you best combat the jitters of starting a PhD? With over a dozen new PhD researchers joining the Rory and Elizabeth Brooks Doctoral College at the University of Manchester’s Global Development Institute, we called upon our existing PhD researchers to ease our new arrivals’ transition.

The formidable panel of Corinna Braun-Munzinger, Sally Cawood, Connie Kang, Lina Khraise, Virgi Sari, Ryo Seo-Zindy, Gaby Zapata Roman, Dani Malerba, Robbie Watt and Bala Yusuf kindly shared their much appreciated insights on the Do’s and Don’ts for the PhD journey.

Make sure you have a life to balance your work from the beginning. The PhD is a new step – unlike previous higher education, there are only a limited number of classes to attend, and most of the work will be self-directed. Consequently, it is easy to fall into unhealthy patterns of working long hours, which can become unproductive. As a result, taking breaks, distancing yourself from work, having friends who have no idea what a conceptual framework is (and frankly don’t care) is vital. But find your own path – you know best what can help you relax, and what can help you work more productively.

Whatever you do, share your thoughts and struggles – whatever you may be feeling, someone else will have felt it before you. Hopefully, that will help you avoid the fates of two of our PhD researchers: one lost all his hair in the first PhD year, and the other realised at one point that she had not talked to her husband for a week!

Data collection

Stay level-headed: it is absolutely normal if things do not go according to plan. As a result make sure you have enough flexibility to deal with inevitable delays, limited access to databases/interviewees, and take advantage of the unexpected opportunities which present themselves.

There is a fine line between making sure you answer your research questions, but also being responsive enough to seize unexpected opportunities. In all likelihood, you will have far more data than you need to write a PhD – the question then simply becomes: which PhD do you want to write?

There are likely to be opportunities to teach, support other research projects and reach out to the community through public engagement in the course of your PhD. Be selective. What you choose to take advantage of should also depend on what you aspire to do after the PhD, helping you develop skills extending beyond your PhD research (teaching, editing, publishing, conference organising, blogging, etc). Make sure your supervisors and other academics are aware of your preferences so they can let you know about suitable opportunities.

Working with supervisors

A PhD is not so different from project management– you have to realise that a PhD is your project, you are managing it, and you are calling upon the help of two trusted consultants (ie your supervisors) when you need their input.

There is a fundamental incongruence: whereas the PhD will be almost your sole focus, supervisors will have a myriad research, teaching, administrative, supervisory, etc, responsibilities. Make sure that you use your time with them well, go into meetings with a clear idea of what you need, and also respect their other responsibilities by not sending them a chapter to read one hour before your supervisory meeting. You need high-quality supervision for guidance, but ultimately, it is your PhD, and you have to write it: you cannot sit in your PhD defence and explain that you only did this because your supervisor told you to. This also means you may have to disagree with your supervisors occasionally. But remember, your supervisors want you to succeed!

Your PhD colleagues are your friends, in more ways than one. They can offer immediate help on things like literature to read or software to use, and most importantly, they will understand the ups and downs of a PhD better than anyone else. Make sure you reach out to PhD candidates outside of your own discipline as well. Everyone will struggle at some point –it is important to share those experiences, and to keep an eye on each other.

Finally, never compare yourself against others’ achievements. Each PhD journey is different.

The PhD experience

While the PhD journey can be trying, it is also important to appreciate it as a privilege: few have the opportunity to spend several years reading, writing and thinking about a topic they have chosen themselves.

Make sure you enjoy it!

A note on the new proposed welfare prediction method for Kenya’s cash transfer programmes

Dr Juan Villa, Honorary Research Fellow, Global Development Institute

During my PhD at the Global Development Institute, The University of Manchester my supervisor, Professor Armando Barrientos, would repeatedly say to me “Juan, you cannot end poverty without learning who the poor are.” Although simple and perhaps colloquial, this phrase summarises why targeting is an important element in the implementation of antipoverty programmes. Apart from measuring general figures on poverty, we truly want to know who those in poverty are to respond efficiently with antipoverty interventions in an environment of scarce resources.

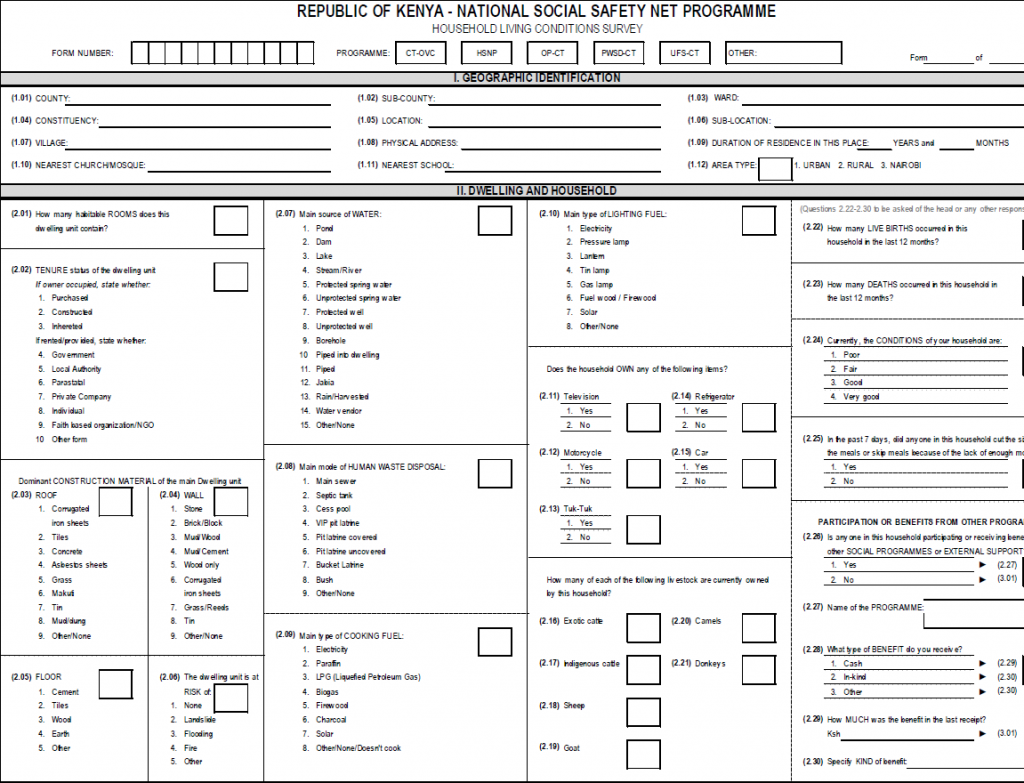

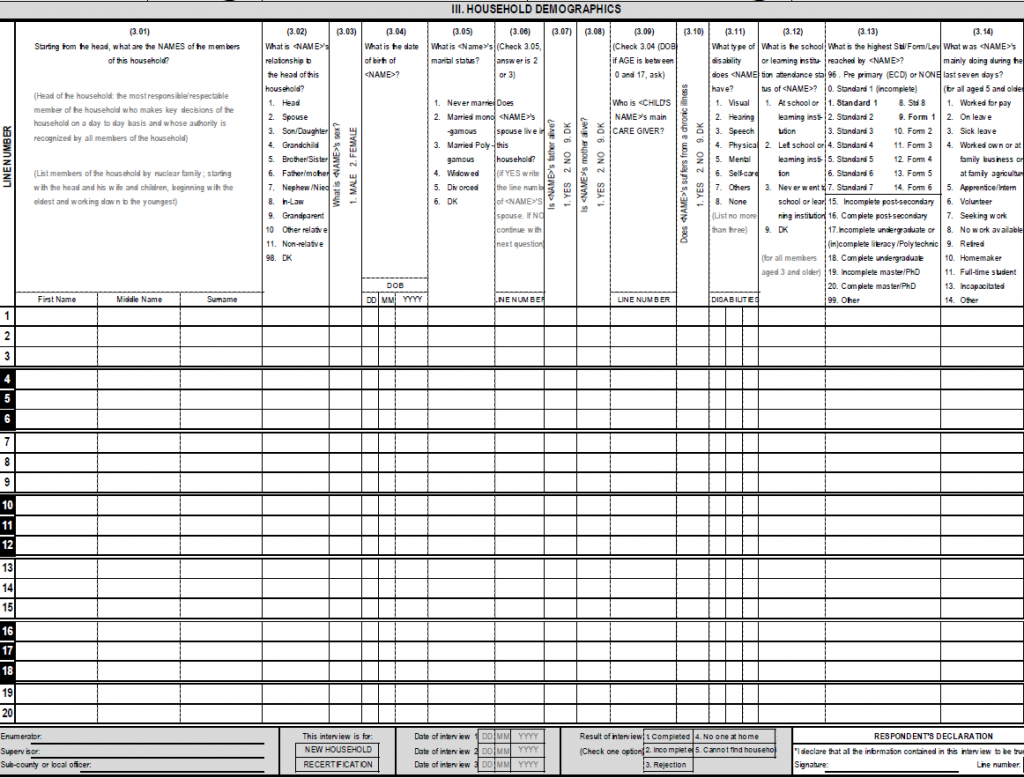

The Government of Kenya is currently implementing four different cash transfer interventions targeted at individuals in poverty and grouped under the National Safety Net Programme (NSNP). The Hunger Safety Net Programme was introduced in four northern areas with support of the UK’s DFID; the Cash Transfer for Orphan and Vulnerable Children currently operates almost nationwide with the support of UNICEF; the Older Persons Cash Transfer and the Cash Transfer for People with Severe Disability (CT-PWSD) were created as national initiatives to protect households with different vulnerabilities. Although these interventions belong to the NSNP, currently they are implemented with independent targeting methods that try to predict household consumption expenditure. Coming back to what Professor Barrientos would say, these interventions intend to discover who the poor are but with different identification tools and four different views of poverty.

I worked alongside with the World Bank and the African Institute for Health and Development (AIHD) in Nairobi to develop a brand new targeting method that would replace those currently used by the four programmes. While it is common to find unreliable income or consumption expenditure information in developing countries, coming up with a new method would require the identification of individuals or households in poverty with a proxy of their welfare.

After reviewing several reports on current targeting practices, I noted that there was general dissatisfaction with the implementation of current methods. These methods were based on a prediction of an official measure of consumption expenditure that allows the construction of general poverty figures, with dramatic imputations of household auto-consumption (dominant in rural areas).

As we were more interested in targeting antipoverty transfers and not in measuring the national poverty headcount, I decided to apply different techniques that provide a proxy for household welfare bypassing the prediction of consumption expenditure. Based on the 2009 National Census data, I proposed a new questionnaire to collect the required information to generate a welfare score which is currently known as the Living Conditions Score (LCS). The LCS ranges between 0 and 100, with 0 being the household with the worst living conditions and 100 the household with the best in terms of dwelling materials, provision of electricity, water and sanitation, household composition and endowment of education attainment. The questionnaire is a two-sided form that can be filled out either manually on paper or with electronic devices:

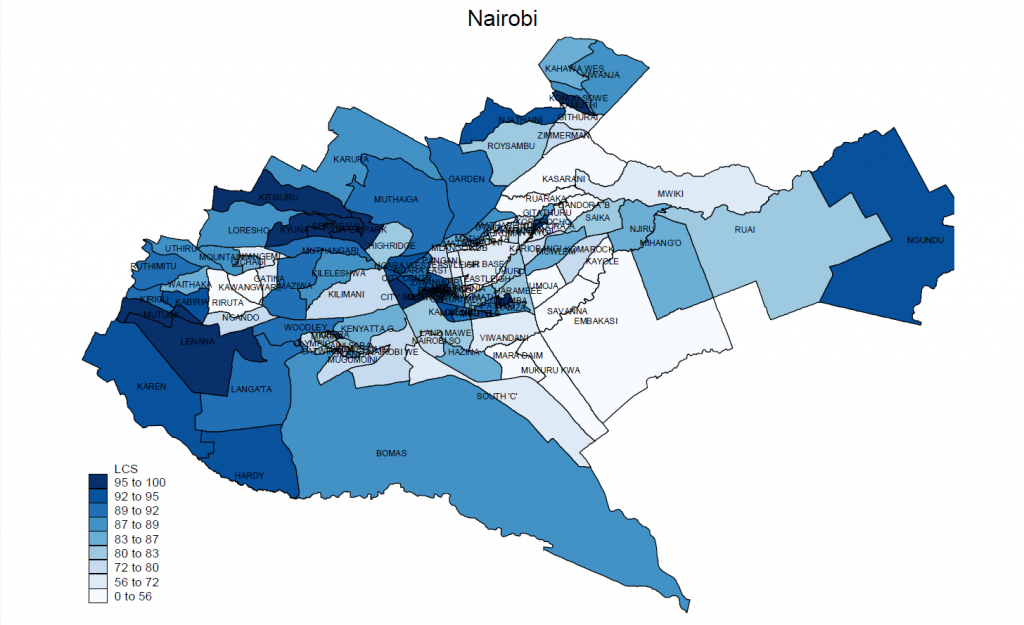

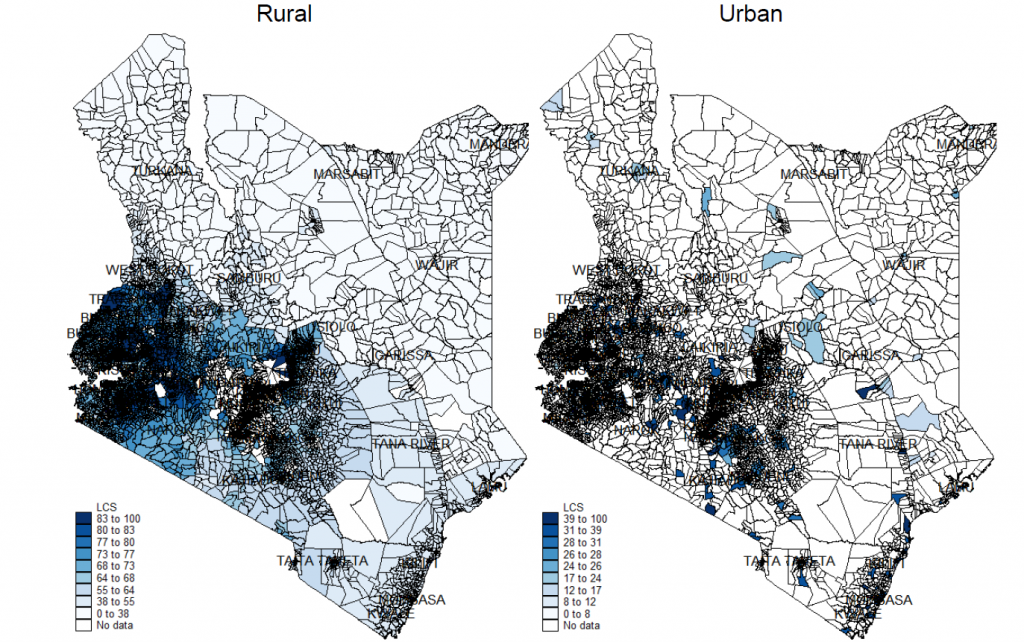

Given its censual nature, the resulting welfare score now allows the mapping of household welfare in Kenya in three geographic areas (Nairobi, rural and urban) with which the government can prioritise certain regions with acute poverty:

The technicalities of the LCS are shown in the paper cited below (or click here). The survey questionnaire and the LCS are being currently piloted by the Hunger Safety Net Programme with the support of AIHD in order to assess its reliability and adaptability with the community component of the targeting process at large. So far nearly 6,000 households have been surveyed with the new method and it is expected that by 2017 it can be adopted by the NSNP.

Several lessons emerged during the development of the new targeting tool for the NSNP. Firstly, the community component in the operation of the programme cannot be ignored. Communities are the most relevant actors in the implementation of the four cash transfer interventions of the NSNP and not allowing them participate in the targeting process with a reliable and objective proxy for household welfare might generate conflict and jeopardise the overall local operation of the interventions.

Secondly, the institutional arrangements are also important. The alignment of the four interventions to use the same poverty identification method was challenging at the beginning. Given the integration of the four cash transfer interventions into one single strategy, agencies and officials are prone to think that such merger could translate into the closing of some of them. After several clarifications the four interventions have agreed to unify their poverty identification methods.

- This blog is based on the working paper “A harmonised proxy means test for Kenya’s National Safety Net programme.”

Will the 2016 drought call time on southern Africa’s sugar fix?

By Professor Phil Woodhouse, Global Development Institute

Across southern Africa governments watch anxiously for signs that the forecast rains will arrive to break the 2015/16 drought that has devastated the region’s economy and left 40 million people, including 40% of the rural population in Malawi and Zimbabwe, facing food shortages that are set to peak next month. Even South Africa, normally a food exporter, is due to import 3.5 million tons of food in the coming months. The crisis throws into sharp relief the region’s need to drought-proof its agriculture, but also increases scrutiny on current investment into irrigation, which has been dominated by one crop: sugar cane.

The sugar industry in southern Africa has increased its output by two-thirds and the (irrigated) land it cultivates by almost 50% over the past 20 years. During this time, three South African companies have expanded their operations across the region where they now account for over 90% of sugar output. In a region where food production is vulnerable to drought, large-scale corporate control of land and water to produce a crop whose consumption is increasingly criticised on health grounds highlights the contradictory forces at work in contemporary African agriculture. An unprecedented collection of papers published this month by the Journal of Southern African Studies explores the dynamics of sugar cane production in seven countries in southern Africa and provides insight into the logic that drives the corporations, governments and local communities involved.

The sugar industry in southern Africa has increased its output by two-thirds and the (irrigated) land it cultivates by almost 50% over the past 20 years. During this time, three South African companies have expanded their operations across the region where they now account for over 90% of sugar output. In a region where food production is vulnerable to drought, large-scale corporate control of land and water to produce a crop whose consumption is increasingly criticised on health grounds highlights the contradictory forces at work in contemporary African agriculture. An unprecedented collection of papers published this month by the Journal of Southern African Studies explores the dynamics of sugar cane production in seven countries in southern Africa and provides insight into the logic that drives the corporations, governments and local communities involved.

While the collection bears out the specificity of different national contexts, some key factors stand out. First, the sugar industry offers to many African governments a tangible opportunity to develop modern agriculture and sophisticated industrial processing to deliver globally competitive products such as sugar and ethanol. Evidence from these studies questions the modernity and productivity credentials of sugar production in southern Africa, as elsewhere, not least in some of its labour practices. However, in pursuit of agricultural and industrial goals, governments make land and water available through special planning zones, protect their sugar markets from foreign imports and endeavour to build a constituency of support among rural communities through ‘outgrower’ schemes.

Second, the historical context is important. The rapid expansion of South Africa’s sugar companies across the region was possible by the liberation of South Africa’s businesses from the constraints of apartheid coupled with the budgetary pressure on neighbouring governments to divest themselves of loss-making sugar plantations. Yet such contexts change. The European Union market to which many southern African countries had privileged access has been reformed in the past decade and the South African sugar companies themselves are now the object of takeovers, including by European sugar refiners.

Against this shifting backdrop of international markets and corporate investment in agriculture, stability may seem a problematic concept. Yet, for southern African governments and rural land users perhaps the key trade-off has been between the stability and steady growth of demand for sugar and the volatility of markets for many alternative (food) crops. This year’s drought and the prospect of changing rainfall patterns associated with climate change suggest this trade-off may need further scrutiny. Sugar cane is a highly water-intensive crop requiring ten months or more of growth before harvest. Even if food is to be imported with cash earned from sugar exports, it is likely to be a very inefficient use of water if irrigation is to underpin the region’s food security. Yet, as these studies show, sugar production is a manifestation of many intersecting interests which reflect the historical and economic context of the different countries in southern Africa, as well as their contemporary political and economic dynamics. Efforts to bring about change must rest on an understanding of each local context.