Gabriele Restelli, PhD Researcher, Global Development Institute

The United Nations recently approved the Global Compact for Migration. This has come shortly after the endorsement of the other compact, for refugees. These agreements have sparked tensions, protests and even a government crisis in Belgium – especially within right wing parties and movements who allege that the controversial nature of these compacts impedes national sovereignty and adversely impacts security.

Although it is hard to understand what is controversial about a non-binding pact to foster international cooperation, it is fair to wonder why the world needs a global compact on migration to begin with. It has often been argued that unprecedented levels of mobility and migration require unprecedented intergovernmental efforts at tackling such a globally relevant phenomenon.

Indeed, in absolute terms, more individuals than ever before are on the move; but that’s simply because the world population has now increased to seven billion. Global migration data show no evidence of discontinuity in overall international migration trends, that is: the total number of people living outside their country of birth (migrant stock) has remained relatively stable as a percentage of the world’s population since 1960, ranging from 3.1% to 3.3% in 2015. Similarly, only 0.75% of the world’s population emigrated in 2014 (migrant flow) – just like in 1995.

People do move, but they largely either migrate within regions or migrate temporarily, with intention to return home. For instance, around 80% of migratory movements from African countries are estimated to happen within the African continent. Similarly, only around 20% of those travelling on trans-Saharan routes report doing so with the intentions to cross to Europe.

Refugees and asylum seekers are no exception. The vast majority (78%) of the displaced population tends to find refuge within their own country (and are labelled as Internally Displaced Persons, IDPs) or in neighbouring countries (becoming refugees). Only a very small proportion of all displaced people across the entire world (3%) travel to European shores.

In the year of the “crisis”, 2015, record numbers of Syrians, Afghanis and Iraqis travelled to Greece and Italy. The total arrivals were slightly more than a million. While it does sound like a huge number, if all the EU countries had offered temporary protection to everyone proportionately to their own population, the whole “European migration crisis” would have been solved with one migrant/refugee/put-your-label-here hosted every 50 thousand citizens. In other words, the whole of Greater Manchester would have contributed to solve the “migration crisis” by hosting only 50 persons: five zero.

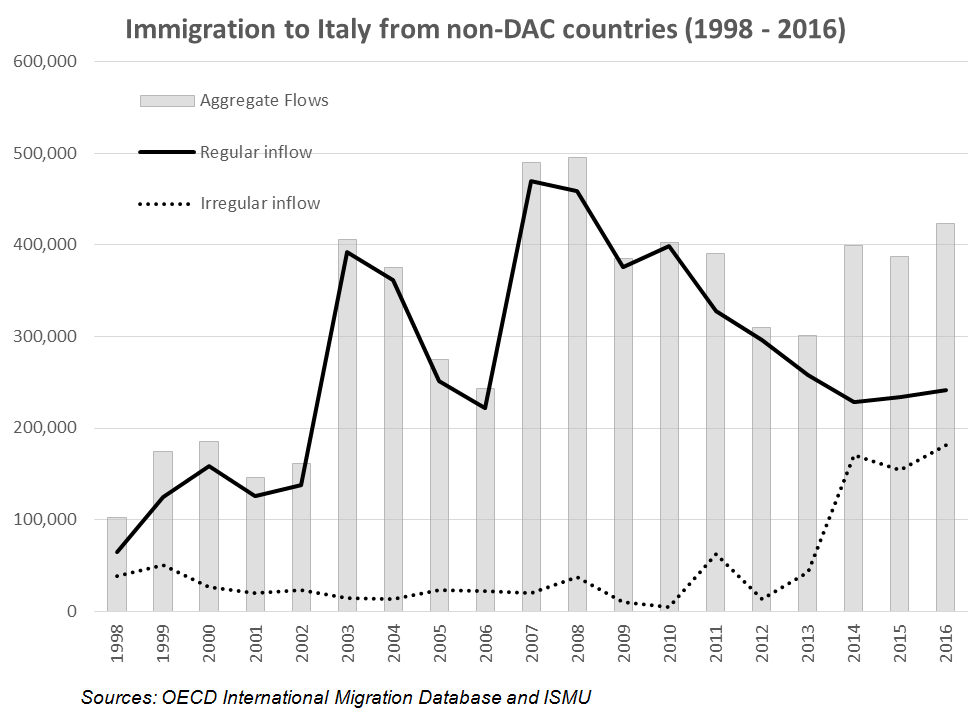

Let’s zoom in on one of the main entry ports to Europe: Italy. The Mediterranean country has often been portrayed as a key example of an EU member state being left alone to suffer the consequences of an unprecedented migration crisis. The graph below shows immigration flows from 1998. It can be seen that there has been no dramatic increase in recent years. In fact, after peaking in 2007 and 2008, immigration has then decreased. However, the irregular component of migration has almost equalled the number of those crossing borders with the required documents.

This perverse relationship between tougher entry policies and increasing irregular migration has been already supported by empirical literature. Rather than reducing the number of arrivals, restricting legal paths is likely to do nothing but deflect flows towards irregular routes.

Then, why has migration become so trendy in the media? Why do we keep seeing boats crossing the Mediterranean like the African continent is about to be emptied?

In Weapons of Mass Migration (2010), researcher Kelly Greenhill posits that migratory movements have been used by states as a coercing tool to obtain more favourable policy concessions from other countries. For instance, Libya’s Gaddafi often threatened European donors to unleash hordes of African migrants had his aid demands not been met.

Migration is used as a policy tool. Through this lens, rather than seeing the negative depiction of immigration as the cause for rising populisms and far-right parties throughout Europe, one could argue that immigration has served as a weapon of mass distraction to achieve policy objectives in other areas. Instead of focusing on, say, rising inequality, declining salaries in real terms, public funding absorbed by private banking system, in almost every European country, the public arena has been hijacked by the debate on immigration. From Brexit to Le Pen, from Germany to Austria, it is evident that immigration has played an increasingly polariaing role.

Going back to the Global Compact, what was thought as a tool to enhance international cooperation towards better migration management, might have just contributed to the misperception and misleading narratives of international migration. As per its potential at actually achieving safer migration, it looks to me that we have now gone full circle. First, governments make it increasingly difficult for migrants and asylum seekers to arrive through regular migration channels. . Second, they watch as those migrants are forced to move via irregular channels and methods and then label this a crisis. Third, they meet multilaterally to discuss how to handle that very same crisis.

Now, imagine a group of pyromaniacs in a forest. After shouting at the fire and calling (blaming) each other for help, they then sit together to discuss how to stop the forest from burning. If you add some pyromaniacs refusing to sit down with others because turning fire off is a matter of national security, there you have your metaphor for the Global Compact(s).

- Photo by Radek Homola on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Very interesting article, friend!!