by Dilek Celebi, PhD Researcher in GDI

On 16 September 2022, a young woman’s murder shook the world. Jîna Amini – a Kurdish-Iranian woman known to the state as Mahsa Amini – journeyed from her hometown of Saqqez (in Kurdistan province) to Tehran. Accused of violating the regime’s compulsory veiling rule, she was beaten by morality police, fell into a coma, and died.

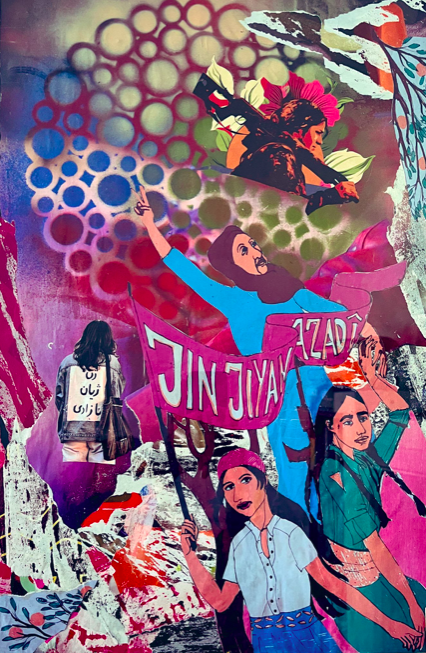

An uprising ensued, quickly swelling from indignation at one woman’s death into one of the largest demonstrations in contemporary Iranian history. The words “Jin, Jîyan, Azadî” – “Women, Life, Freedom” – became its rallying cry, referencing Kurdish feminist politics while embracing the common hunger for dignity, justice, and self-determination.

As we approach the third anniversary of the murder and uprising, it’s surely time for us as academics to reflect on Jîna Amini’s legacy and wrestle with questions about the difficulties of organising under autocratic regimes.

In spite of years of authoritarian repression within Iran, why was one individual’s death greeted by countrywide and even international responses? The answer isn’t necessarily complex: it was the drop that caused the glass to overflow. But within that overflowing drop was something more—a reckoning between the Iranian Kurds and the Iranian state. In other words, beyond the authoritarian character of Iran’s regime, it exposed the limits of ethnicity within a colonial structure.

This short paper evaluates the Jîna uprising through the lens of three major gains and three major failures, offering a balanced account of its record.

Three Gains

1. A New Discourse of Resistance

Perhaps the deepest gain of the Jîna uprising was that it was able to alter the discourse of political resistance in Iran. For several decades, protest in Iran has mainly focused on three themes: economic grievance, political reform, and anti-authoritarianism. Economic protest includes riots in Mashhad in 1992, gasoline riots in 2007, and national rallies in 2017-2018 that started with protests about rising inflation and austerity. Reform activism was first perceptible with student protest in 1999 and Green Movement protest in 2009, with calls for freedom of the press and transparent election. Anti-authoritarian activism ranges from revolutionary outcries against the Shah in 1978-79 through to “Aban protest” of 2019, when demands for regime change were coupled with complaints about fuel costs. Taken together, these instances reflect how Iran’s protest track record has forever alternated between legal demands, reform hopes, and overt oppositions to authoritarian rule. Although most of Iran’s previous rebellions were intense, contentious, and prolonged, Jîna was unique in that it was capable of extending its coverage and visibility outside of Iran’s borders, reaching out to people worldwide and touching a chord in them. Also, the Jîna uprising broke this model by centring gender liberty at the heart of resistance. Women took centre-stage—cutting off their hair, burning their headscarves, and facing security forces eyeball to eyeball. The slogan “Women, Life, Freedom” comprised a new model in which bodily autonomy, feminist resistance, and communal pride became inseparable from democracy activism. Even in loss, this symbolic redirection is a long-term legacy. This was the beginning of women-led resistance against injustice.

2. Solidarity Across Divides

While the uprising was triggered in the Kurdish town of Saqqez, it quickly spread into Persian, Baluchi, Azeri, and other areas. For years, Kurdish political voices have often been dismissed—by the regime and by much of Iranian civil society—as separatist (though self-determination is a legitimate right, but that is for another piece). Nonetheless, during the uprising, that label lost much power. The slogans, images, and symbols of Kurdish resistance were accepted across Iran as part of communal resistance, not as a plea for Kurdish legitimacy, even as some extremist groups sought to push down, co-opt, or manipulate the Kurdish voice in Iran and internationally.

What made this solidarity distinctive was its breadth and inclusiveness. It brought together citizens from across divisions of ethnicity, gender, religion, and class—from workers and students to artists, professionals, and communities whose names are not always remembered in the pages of public discourse. The uprising wove together multiple grievances: patriarchy, state repression, economic exclusion, and ethnic exclusion were all challenged under the banner “Women, Life, Freedom”. This moment did not remove long-held mistrust or structural inequalities, yet it showed how Kurdish-led activism and broader national aspirations might overlap. In this way, the Jîna uprising illuminated the existence of a transgressive solidarity that passed through hardened boundaries.

3. Global Visibility

The uprising attracted unprecedented international coverage. Iranian diaspora networks organized protests in world capitals and other major cities, and transnational feminist networks employed the slogan “Women, Life, Freedom.” Media coverage, online activism, and transnational campaigns for human rights placed Iran’s internal repression irrevocably under a spotlight. This international broadcasting not only forced governments to issue condemnations but also built a transnational archive of resistance, ensuring that the uprising would not be forgotten even while repression solidified inside Iran.

Three Failures

1. Inadequate Organizational Infrastructure

Despite its passion and creativity, the uprising lacked organizational scope enough for transfiguring demonstrations into long-term political change. There was no centralized figurehead, no planning committee, and no chart of negotiation or escalation. There were several attempts to achieve unity, including Reza Pahlavi’s attempt to mobilize the diaspora against the current regime. However, the initiative was widely perceived as reproducing elements of authoritarian control at another level, ultimately limiting its effectiveness. The movement’s horizontal and non-hierarchical structure fostered spontaneous participation yet also limited its potential for endurance. In the face of a highly structured and military regime, this failure of long-lasting infrastructure became a death blow.

2. Intense State Repression and Fragmentation

The Iranian regime deployed deadly force. Hundreds died, thousands were detained, and surveillance capacities were increased. Universities, workplaces, and residential areas were systemically purged of opposition. Activists went into exile in droves, breaking the movement’s momentum inside Iran. The repression not only drained the uprising’s capacities but also validated and strengthened fear and mistrust, further inhibiting the development of resistance networks in the short term. Alas, the cycle of repression did not cease: even today, individuals are detained or disappeared by force in Iran for participating in, or belonging to, the Jîna uprising.

3. No Concrete Policy or Regime Shift

One of the key limitations of the uprising was the absence of tangible political change. Core state institutions remained intact, and existing structures of clerical authority, military power, and centralized governance continued to dominate. Although there were temporary signs of relaxation in dress-code enforcement, these proved short-lived. As seen in many non-pluralist political systems, translating grassroots mobilization into concrete policy concessions is structurally difficult, and the Jîna uprising underscored these broader constraints. While the subsequent passage of the Mahsa Act indicated international recognition, in practice it largely reinforced the influence of particular groups within the diaspora rather than producing substantive change on the ground.

The Jîna uprising of 2022 was a breakthrough and a tragedy. It rewrote Iran’s symbolic politics, forged a sense of solidarity between and beyond ethnic and class boundaries, and attracted global attention. But it imploded in the face of brutal repression, organizational fragility, and the persistence of authoritarian power.

Its legacy therefore lies less in change and more in the imagination it sparked—a prospect of an Iran in which women’s emancipation, ethnic equality, self-determination and human dignity converge.

More broadly, the uprising illustrates a discouraging yet significant reality: popular uprisings in autocratic states have far less chance of success than similar uprisings in liberal democracies, in which institutional pluralism, a free press corps, and legal protections can amplify and translate grievances into real-world change.

The Jîna uprising, accordingly, is simultaneously an inspiration and a lesson—illustrating the power of popular mobilization while exposing the vast limits that exist due to consolidated autocracy. And yet it is one of the most inclusive and diverse uprisings of the contemporary world, one that emerged from the “East.”

Top image by @labyrinthberlin on Instagram (shared with permission)

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academic featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.