by Saumik Paul (Senior Lecturer in Global Development, GDI) and Andy Sumner (Professor of International Development, KCL)

Understanding inequality trends remains central to assessing both development progress and global justice. Two major dimensions—inequality between countries and inequality within countries—have long structured debate in development studies.

In the 1990s, Lant Pritchett’s provocation that the world was experiencing “divergence, big time” captured the mood of an era in which income gaps between countries were seen to be widening. More recently, the “converging-divergence” thesis proposed by Horner and Hulme in late 2010s argued that while inequality between countries was declining, inequality within countries was on the rise. In this blog, we argue that something new has emerged over the last decade akin to a flatlining or plateauing.

Inequality between countries

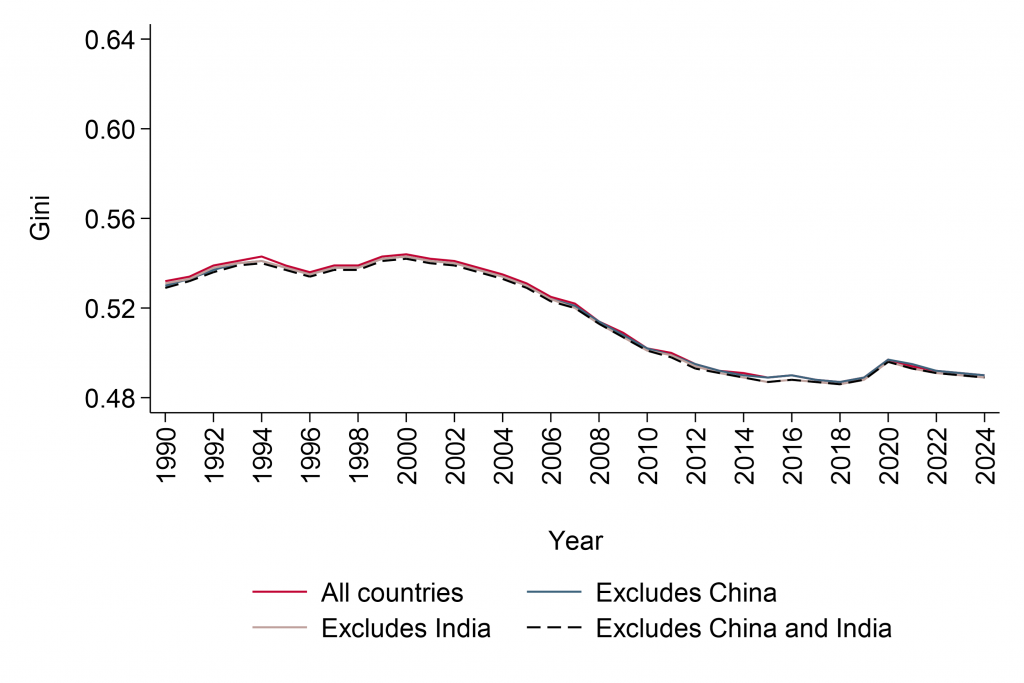

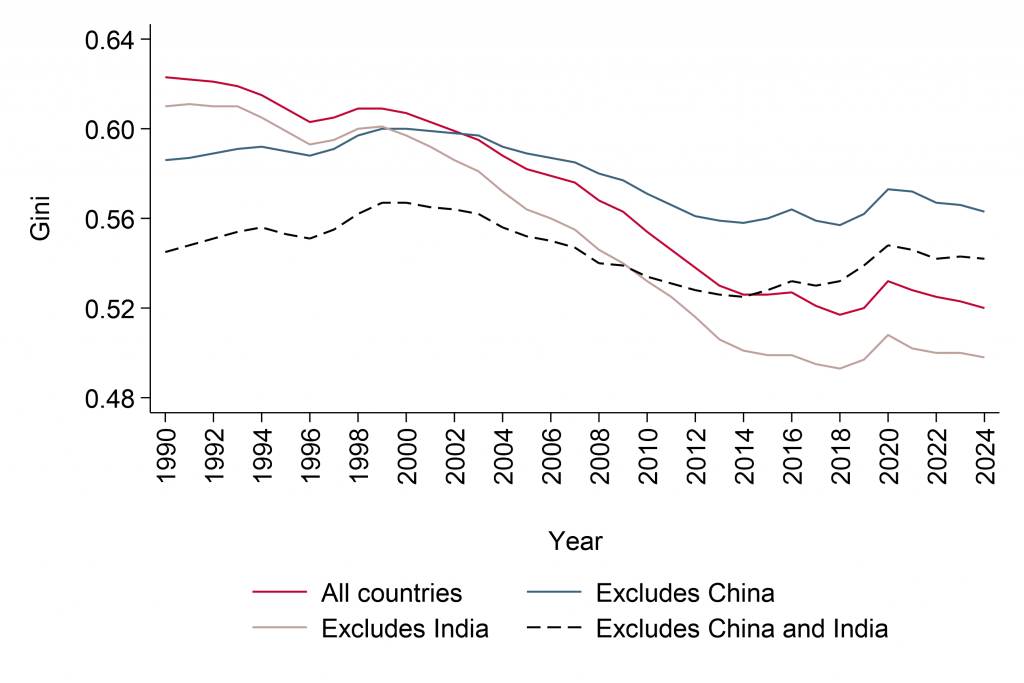

Starting with inequality between countries, it is important to distinguish between two commonly used measures. International inequality refers to differences in average per capita income between countries, treating each country equally regardless of population size. In contrast, world inequality adjusts for the size of countries’ populations, thus giving greater weight to populous countries such as China and India. Between 1990 and approximately 2015, both measures suggest a pattern of convergence overall.

International inequality – the population unweighted Gini coefficient – declined from around 0.60 in 1990 to 0.52 in 2015, but has since flatlined for almost a decade. World inequality – the population-weighted Gini – fell more sharply over the same period, from around 0.68 to 0.44 but it too levelled off in the years after 2015.

The convergence overall, though, is highly contingent on the trajectories of China and India. Once these two countries are removed from the population-weighted analysis, the world Gini coefficient shows no such decline. In fact, it increases from approximately 0.55 in 1990 to over 0.62 by 2024. This pattern is clearly visible in Figure 1 (panel B), which charts between-country inequality with and without China and India. What appears as convergence in aggregate is largely an artefact of rapid income growth in just two countries. In their absence, the trend is one of hidden divergence, underneath the headline of convergence.

Figure 1. Between-country Inequality with and without China and India, 1990-2024

A. International inequality (Gini, unweighted)

B. World Inequality (Gini, weighted)

Source: Authors’ estimates based on the Poverty and Inequality Platform data, World Bank.

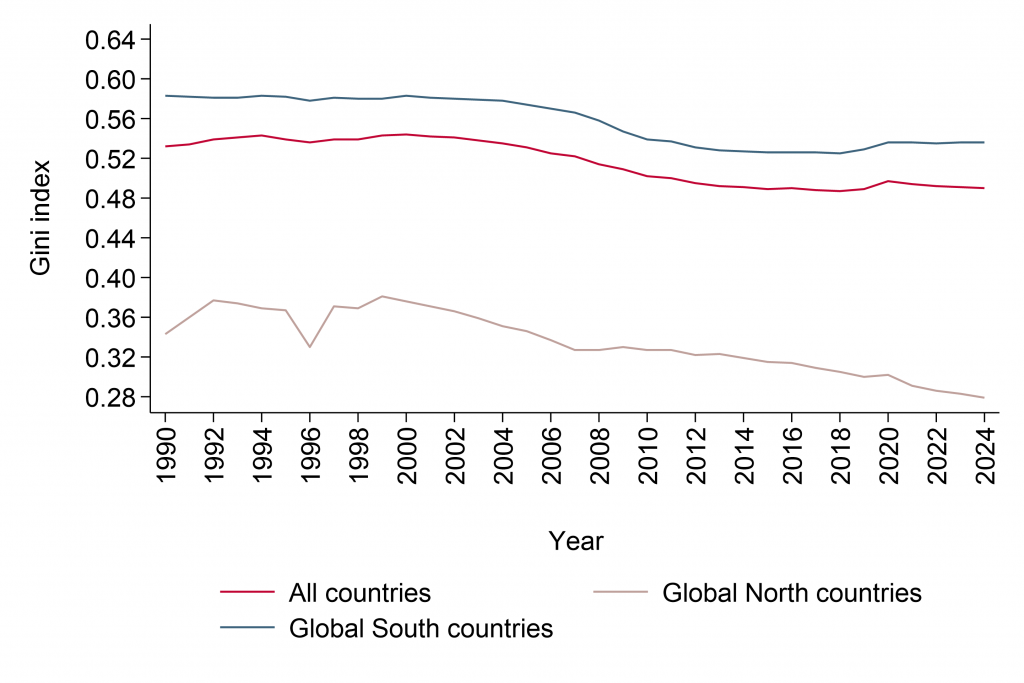

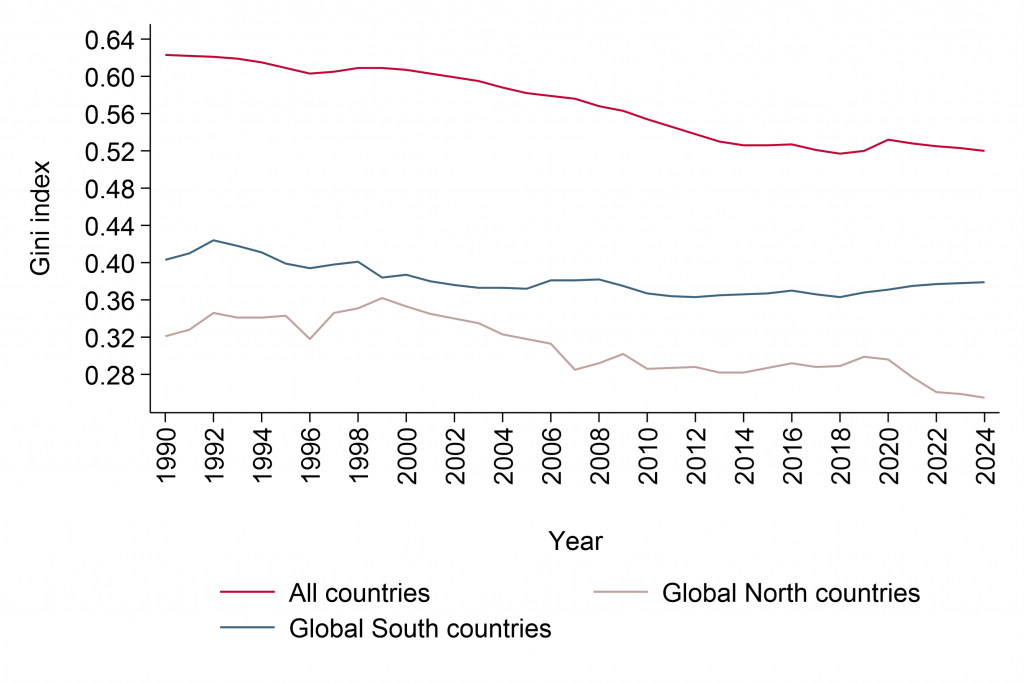

Further, as Figure 2 shows, inequality between countries within the Global South declined modestly from 1990 to around 2015 and has since stabilised. This trend is visible in both the unweighted and population-weighted Gini measures. The decline reflects the growth of a subset of middle-income countries that gradually narrowed the income gap with the better off countries of the Global South. However, this process has not continued in the post-2015 period, suggesting that convergence within the South itself has stalled and that large income differentials persist across the group of countries within the Global South.

Figure 2. Between Country Inequality in Global North and Global South, 1990-2024

A. International inequality (Gini, unweighted)

B. World Inequality (Gini, weighted)

Source: Authors’ estimates based on the Poverty and Inequality Platform data, World Bank.

In contrast, inequality between countries within the Global North has fallen slowly and steadily over the same period. This may reflect a degree of economic synchronisation among advanced economies, and perhaps the stabilising effects of regional integration (e.g. within the European Union), common institutional frameworks, and slower growth in leading economies relative to laggards. Yet the overall variation within the countries of the Global North remains lower than that within the countries of the Global South.

The broader point is that inequality between countries within both groups is now relatively stable. In the Global South, this suggests that the period of rapid catch-up by some economies may have reached its limits, at least under current global economic conditions. In the Global North, falling inequality among countries may indicate structural convergence around low-growth levels. In both cases, the stability implies that future reductions in global inequality may depend less on South–North convergence and more on narrowing gaps within each country group.

This trend also raises a further issue: the levelling-off of between-country inequality within both the Global North and within the Global South reinforces the need to re-centre within-country inequality and redistribution as a central concern in development studies.

So, what about within-country inequality?

Turning to inequality within countries, the picture although mixed also suggests a flattening trend in recent years.

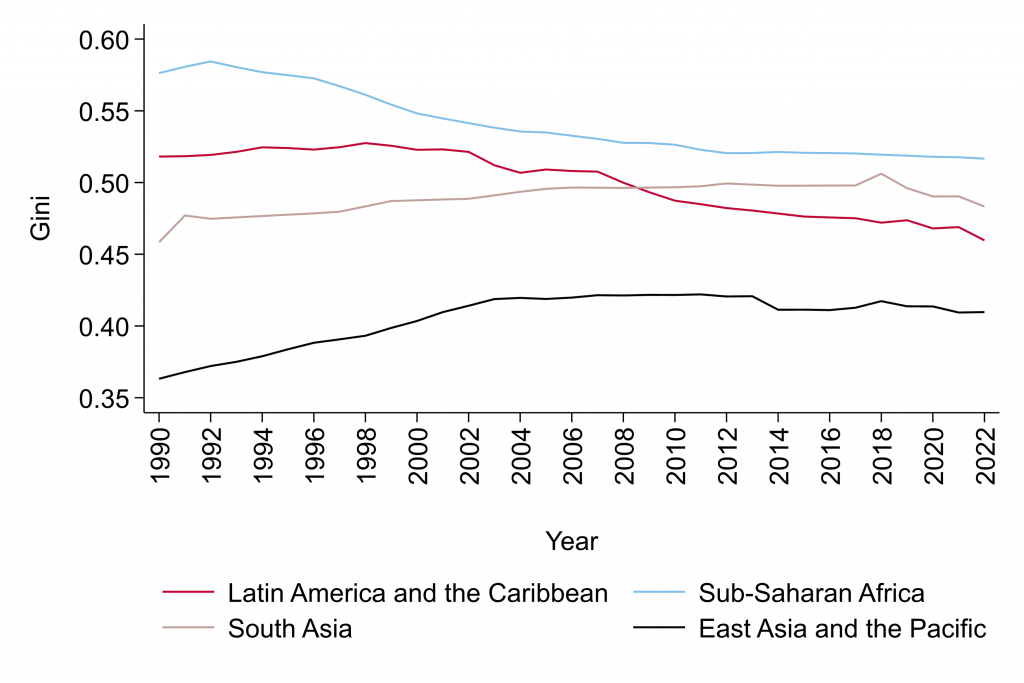

Figure 3 compares the regional population weighted average of within-country inequality across four regions. From 1990 to the early 2010s, Gini indices rose in regions such as East Asia Pacific (EAP) and South Asia (SA). At the same time, inequality within country fell in Latin America (as is well-known) and (as is less well-known) fell on average in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA), though it’s important to note that this was from exceptionally high levels in both those regions. Also, less well-known and only evident in standardised income data – thanks to UNU-WIDER – is that the most unequal countries in the world are not in Latin America but in sub-Saharan Africa.

Figure 3 Within-country Inequality by region, 1990-2022

Source: UNU-WIDER, World Income Inequality Database (WIID) Companion dataset (wiidcountry and/or wiidglobal). https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/WIIDcomp-300622.

Since about 2015, within-country regional averages have remained largely flat with the exception of Latin America, in which the average Gini declined very modestly. South Asia also had some modest decline. In East Asia, inequality plateaued. OECD countries, meanwhile, have maintained an average Gini of around 0.32 throughout the period, meaning countries across the Global South typically contend with much higher within-country inequality than the richer countries.

So, what to conclude?

Taken together, these findings suggest that inequality between and within countries has entered a new era which you could call ‘flatlining’ or ‘plateauing’. While both terms suggest little progress or even stagnation, they carry distinct meanings and implications. Flatlining conveys a total stop in progress, often with the sense that recovery may be unlikely or serious intervention is required. In contrast, a plateau indicates a pause that may be temporary, where improvement remains achievable if conditions shift or strategies are revised. We don’t know for sure, but it seems more likely to be that between- and within-country inequality have hit a flatline rather than a plateau given the growth outlook and the recent shockwaves sent through the global economy by President Donald Trump. This remains to be seen, however.

What we can be sure of is that the situation changed about ten years ago. Between-country inequality flatlined, while within-country inequality stagnated. The period of global convergence driven by China and India appears to be over. Maybe a global inequality ‘boomerang’ is coming given some of the underlying dynamics.

For illustration, Kanbur et al ask: What conditions would be necessary to achieve a reduction in income inequality, whether between countries, within countries, or both? One pathway that could reduce inequality within countries is industrialisation, especially through a rise in manufacturing employment—historically linked to more equitable income distribution. However, many middle-income countries are already undergoing or are projected to undergo deindustrialisation in terms of employment, which may raise within-country inequality.

A more direct route would be the adoption of social and economic policies specifically designed to reduce inequality within large middle-income countries. Yet, there is little evidence of political momentum toward the election of governments to support the politics necessary for with strong redistributive agendas in these contexts.

One important but final point – these estimates do not account for top income adjustments, which would very likely raise within-country inequality levels though maintain the same trends at a higher level of inequality (more on that in a future blog revisiting the ‘Palma proposition’ that inequality is a struggle between the richest and the poorest for share of national income). Nonetheless, the apparent flattening of both dimensions is notable and deserves greater attention in contemporary development studies and policy.

For development studies, the implications are important. First, the convergence narrative post-Cold War is somewhat fragile given what happens when China and India are removed from the analysis. Second, a new era has emerged as both dimensions of inequality have stabilised at still very high levels, which marks a new and potentially more politically intractable era. The policy challenge ahead is not only about how to resume convergence, but also to tackle entrenched inequality within societies.

Top image by Christine Roy on Unsplash

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academics featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.