by Louisa Hann

The exploitation of workers and the governance of decent work in global value chains (GVCs) represent long-standing issues spanning Development Studies, Political Economy, Economic Geography and International Business. While private and public ethical standards have done something to address problems like poor wages, lack of workplace security, and lack of social protection within global value chains, there’s still a long way to go before the world realises the UN’s 8th Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) – to promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all.

To address this problem, much inter-disciplinary scholarship on globalisation and value chains has focused on private governance of decent work led by firms in the global North benefiting from producers in the South – a dynamic precipitated by histories of uneven development and colonial exploitation. This literature tends to draw binaries between ‘hard’ (i.e., strict and compulsory) and ‘soft’ (i.e., voluntary and loosely enforced) forms of governance, typically conflating ‘public governance’ with ‘hard’ legislation. However, a fast-changing geopolitical environment and shifting domestic trade priorities mean the geographies of value chains are evolving across the world, raising questions about such distinctions and the governance of decent work.

In Africa, for example, the number of retailers selling products within regional and domestic markets is growing quickly in line with the rise of continental trade agreements. At the same time, President Donald Trump’s recent populist trade imperatives have thrown hegemonic trade practices and the dynamics of globalisation into question. Whether or not Trump’s protectionism ends up reshoring some GVCs, growing end-markets in the global South mean instances of South-South trade already surpass those of North-South trade, illustrating the mutability of globalisation’s contemporary political economy.

So, what does this mean for academic scholars and policy actors tracking the governance of decent work, especially in Southern contexts? A new article by authors including the University of Manchester’s Matthew Alford, Stephanie Barrientos, and Khalid Nadvi, recognises that our understanding of decent work governance in regional and domestic value chains (RVCs and DVCs) remains very limited.

In a bid to start addressing this problem and provide a framework for future research, they interrogate the complexities of governing decent work within RVCs and DVCs. While analysis of governance within GVCs has benefited from analysis of their multi-dimensional power dynamics and the mediating role of states and civil society actors,

“We have relatively limited understanding of governance, orchestration and power dynamics in RVCs/DVCs located within and led by actors from regions and countries in the global South. This knowledge gap is problematic. Not only do we find that GVCs increasingly intersect with RVCs and DVCs, but also that end-markets governed by lead firms in the global South are increasingly prominent trade outlets. Collectively, these emergent trends have profound implications for the public and private governance of decent work.”

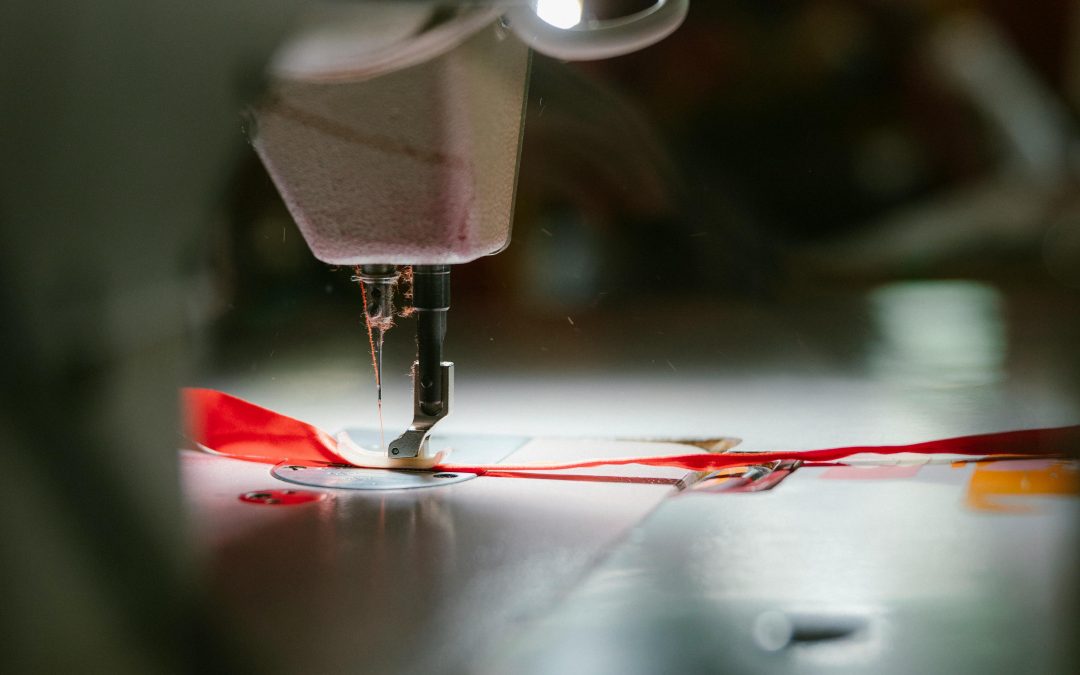

Turning their attention to analysis of horticultural and garment RVCs and DVCs in Sub-Saharan Africa, the authors identify relatively weak private governance of decent work within these chains. For example, workers in South African garment factories have historically benefitted from very strong trade union representation and well-established bargaining arrangements. However, garment retailers have been undercutting governance structures within the industry by establishing factories in Lesotho and Eswatini that pay workers much lower wages. At the same time, cheap garment imports from China also undermined the organisational power of South Africa’s garment workers.

This trend exemplifies what the authors identify within the horticultural and garment sectors as the limited enforcement of strict labour legislation, combined with a growing reliance on competition-driven informalisation, undermining existing work norms. ‘If left unchecked’, they warn, ‘this could significantly undermine any attempts to effectively bring about a successful transition to effective public (and private) governance of decent work goals.’ But how are governments addressing decent work deficits? And how can they coordinate both public and private actors to achieve such goals?

To better appreciate the intersections between private and public governance of decent work, the paper presents a framework for understanding these structures on a ‘governance-power continuum’ that ranges from ‘directive’ to ‘facilitative’ public governance – a move away from more binary modes of analysis. By providing a framework to appreciate increasingly heterogeneous forms of public governance, the paper lays the groundwork for future research into the evolution of the public governance of RVCs and DVCs in an era defined by ongoing political tensions, as well as the further study of cross-border due diligence regulations.

Read (Open Access): ‘Private and public governance of decent work in regional and domestic value chains: the case of horticulture and garments in Sub-Saharan Africa‘

Top image by Hong Son

Note: This article gives the views of the author/academics featured and does not necessarily represent the views of the Global Development Institute as a whole.

Please feel free to use this post under the following Creative Commons license: Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0). Full information is available here.